Apart from Tokaj, some other Hungarian wines are also worth the attention despite flying under the radar internationally.

Unlike beer, wine has been essential all throughout Hungary's history: wine was a key export and a vital sustenance available to rich and poor alike. Today, still, Hungary is a major wine producer globally with a total of 22 wine regions and 63,000 hectares (156,000 acres) of planted vines. Most of the country's vineyards are considered to be cool-climate and occupy the northeastern segment of Europe's wine-growing region. The most famous wines in Hungary come from Tokaj, home to the world's oldest classified wine region.

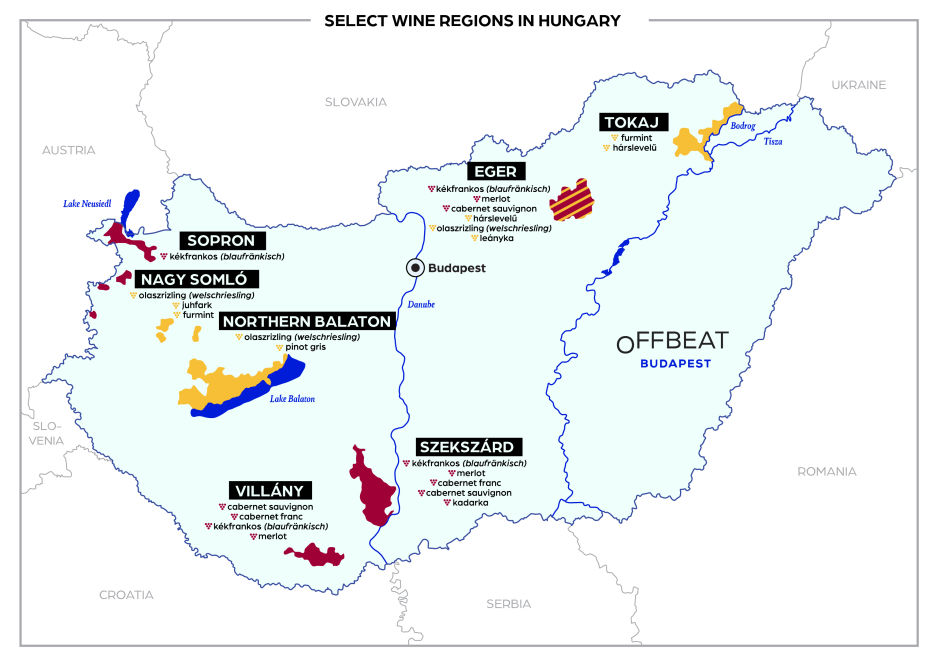

Click here to expand the wine map.

A little wine history

Winemaking in Hungary goes back to the Romans — likely even to the Celts, the previous occupants of the land — who planted grapevines around the scenic Lake Balaton in what's western Hungary today. This means that vineyards had long existed before the Hungarian tribes conquered the area in the 9th century CE. Initially, medieval Hungarian kings entrusted the Benedictine order with viticulture, relying on the monasteries' long tradition of winemaking.

In the 12-13th centuries, German, French, and Italian settlers brought improved craftsmanship to many regions. Things ground to a halt when Ottoman Turkey invaded southern Hungary in the 16th century: people left their vineyards, the population declined, years passed without a harvest. This was when new winemaking centers formed in the unoccupied north, most notably in Sopron and Tokaj.

Soon, Tokaj became well-known across Europe. By the late 17th century, popes, emperors, and Russian czars were among the admirers. The golden-hued sweet aszú wines, which are made with the help of a benign fungus, were used even to curry political favors: Ferenc Rákóczi II sent shipments of Tokaj to the Palace of Versailles to coerce Louis XIV into funding his war of independence against the Habsburgs.

Hungary's wine industry flourished after the formation of Austria-Hungary in 1867. Thanks to better techniques and access to a bigger market, Hungary became the second largest wine producer in Europe behind France.

Tragically, as elsewhere in Europe, the phylloxera plague wiped out two-thirds of Hungary's vineyards by the end of the century. Many winemakers lost their livelihoods and, in despair, emigrated to the United States. Others started life anew on the sandy vineyards of middle Hungary: the deadly insects couldn't survive in sand so people planted wine grapes on huge swaths of land there.

It was also around this time that local vintners replaced native Hungarian grapes like gohér and járdovány with foreign varieties that were considered to be better and more resistant to diseases. Some of them, like cabernet franc, went on to thrive in Hungary’s sun-drenched southern soil.

During the four decades of Communist rule (1948-89), state-owned cooperatives nationalized most vineyards and planted new grapes on low-lying lands that were suitable to harvesting machines. Quantity trumped quality, but the mass-produced stuff found plenty of eager customers within the Eastern Bloc. In the meantime, many family winemakers abandoned their high-quality sites on the hillsides in the face of economic and political headwinds.

The current day

After the fall of Communism, local growers had to start with a clean slate and improve the standards. From the 1990s, the capitalist era set off a revival: locals turned to Hungarian wines with renewed interest while small family wineries sprung up at a head-spinning pace.

Mirroring global trends, burly, powerful wines with a pronounced taste of new oak barrels were prominent in the early aughts. Since then, the pendulum has swung back; today, less intrusive techniques leave more room for the soil and grapes to shine through and natural and orange wines appear on many Budapest wine menus these days.

Internationally, Hungary has found it difficult to carve out a niche for itself and most of its wines remain unknown outside the country. How come? Sweet wines aren't currently fashionable so Tokaj has lost some of its market (few people know that Tokaj also makes dry wines). And foreign varieties struggle to convey a sense of place — it's hard to get excited about a Hungarian cabernet franc, no matter how good it is. But this may be just fine. Hungary's wine consumption per capita is one of the highest in the world, and locals happily drink away most of what’s produced.

Classifications

Hungary's labyrinthine wine classification system doesn't make things easy for a novice. Wine regions aren't indicative of specific grape types, unlike in Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Tuscany for example. Case in point: both Tokaj, in eastern Hungary, and Somló, in the west, produce wines from the furmint grape. You’re best off seeking out specific winemakers or regions (the below summary and this page will help you get started).

5 major wine regions

There are 22 official wine regions in Hungary but most top wines come out of a handful of areas.

Tokaj: Hungary's best-known wine region consists of a group of 27 historic villages in northeastern Hungary and many of the country's top wineries. Two native grapes, the volcanic soil, and a unique microclimate that triggers the apeparance of a benign fungus make the wines here special. It was the sweet aszú that made Tokaj famous in the 17th century, but today the region, which is well worth visiting, is also putting out dry wines and pezsgő.

Eger: The volcanic mountain ranges in northern Hungary can produce wonderfully savory wines, both red and white. Most prominent is the area around Eger, home to producers of the Bull's Blood (Bikavér) blend.

Sopron: Located on the border with Austria in Western Hungary, the limestone and slate hills facing Lake Neusiedl (Fertő tó) produce some of the country's top kékfrankos (blaufränkisch). A few winemakers in Sopron, which is known as the "Capital of kékfrankos," are starting to rival the better-known producers across the border.

Northern Balaton & Somló: The main pull of this panoramic wine region in western Hungary is the breathtaking vistas over Lake Balaton and the adorable medieval villages and small growers lining it. The vineyards are planted with white grapes, especially olaszrizling (welschriesling), and scattered across softly rolling valleys and volcanic hills. Somló, a bit away from the lake, is swarming with family winemakers on tiny plots.

Villány & Szekszárd: Many red wines come from the warmer regions in southern Hungary. Villány, just a stone’s throw away from the Croatian border, is home to big, bulky, and often beautiful reds. Not far from there is Szekszárd, home to the kadarka grape. Franz Liszt was so fond of the delicate and spicy kadarka wines that he visited Szekszárd several times.

Grape varieties

Historically, Hungary has been a white-wine country (red wines appeared only in the 17th century with the kadarka). Today, still, two-thirds of Hungary's wines are white by volume, but whites and reds are about equally represented within the premium segment.

4 major white grapes

Furmint: Furmint's natural home is Tokaj where it makes both sweet aszús and dry, minerally wines with a racy acidity. Its crispy, salty, acid-forward flavor profile is often compared to a chenin blanc. The Somló region also produces furmints and it can be interesting to compare those to Tokajis.

Hárslevelű: Tokaj's number-two grape, which often serves as the yin to furmint’s yang – these two traditionally partner in Tokaj blends, both sweet and dry, where the hárslevelű’s lighter and floral notes nicely round out the bright acidity of furmint.

Olaszrizling (welschriesling): Despite its moniker, olaszrizling has nothing to do with the riesling from the Rhine region; instead, it's a regional grape that appeared in Habsburg wine-making lands in the 19th century (in Croatia it’s known as grasevina). With an approachable acidity and characteristic hints of almond, it's often a crowd-pleaser. The best ones tend to come from northern Balaton.

Juhfark: The name of this grape means “sheep’s tail” in Hungarian because that's what its long, elongated clusters resemble. Today, juhfark is only planted in Somló, where it's one of the few native grapes that survived the phylloxera epidemic of the late 19th century. Juhfark has a deeply minerally, salty character and a bit of aging and residual sugar can nicely take its edge off, if so desired.

3 major red grapes

Kékfrankos (Blaufränkisch): Hungary’s most planted grape accounts for forty percent of all red grapes in the country and hence appears in many wine regions. Better known as blaufränkisch, it’s also common across Hungary's border in Austria's Burgenland region. At its best, kékfrankos is medium-bodied with hints of cherry and spices. “If a comparison had to be made, kékfrankos is not unlike a Cabernet Franc or a Syrah from a cooler region,” said one of Sopron’s leading winemakers, Franz Reinhard Weninger, who has vineyards on the Austrian side too. The top kékfrankos tend to come from Sopron, Eger, and Szekszárd.

Bikavér (blend): Also known as Bull's Blood, this blend rightfully had a bad reputation during the Communist era – a critic once called it “a watery insult to bulls everywhere.” But today, complex and layered Bikavérs come out of wineries in Eger and Szekszárd. The blend contains at least four grape varieties; the main component is kékfrankos (blaufränkisch), with traditional Bordeaux grapes such as cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, and merlot rounding out the flavors.

Kadarka: Balkan settlers from Ottoman Turkey introduced the grape in southern Hungary in the 16th century. Kadarka makes easy-drinking light red wines with low tannins and fruity, sometimes spicy notes. It doesn’t age too well and it's a troublesome grape – its thin skin is prone to rot and it ripens late – so much of it disappeared from Hungary throughout the 20th century. Today, the best kadarkas come from Szekszárd and Eger.

Tokaj’s aszú wines

Louis XIV of France should be credited with crafting the most enduring advertising slogan in the history of Hungarian wines by calling Tokaj "the wine of kings and the king of wines." But what's all this fuss about Tokaj?

Starting in the 16th century, local winemakers enlisted the help of a friendly fungus called botrytis cinerea, known as the “noble rot,” which can attack the grapes and leave behind shriveled berries with a naturally intensified, sweet-tart flavor. While munching away, the fungi create a host of new flavors and intense aromas – apricot, orange, honey – that make their way into the wines. Grapes so infected are called aszú, and aszú wines are the heart of Tokaj’s sweet wines. Other well-known wines that rely on this mold include Sauternes in France and Beerenauslese in Germany.

Harvesting for aszú is hard: laborers need to pick the aszú grapes individually off the bunch. On an average day, they may pick eight kilos of aszú compared to 500 kilos of regular grapes by the cluster. Of course, these desiccated grapes hardly contain enough liquid to make a wine, so winemakers soak them in a base wine for a day or two to extract their flavors.

Historically, laborers collected the aszú grapes in a carrying basket called puttony, and depending on how many puttonyful of aszús landed in a 136-liter barrel (Gönci barrel) filled with base wine, the wine was assigned a puttony-rating. Today, five and six-puttony aszűs exist, but not all winemakers elect to put them on the label because it can confuse drinkers unfamiliar with the intricacies of Tokaj winemaking. An aszú bottle without a puttony-label is by default a five-puttonyos.

Despite the natural fruit sugar present in these wines (stuff that didn't ferment into alcohol), aszú wines aren't cloying because of the high acidity. “Sweetness so balanced and held in check by the sharp-tasting furmint that they leave your mouth whistle-clean,” wrote Hugh Johnson, the famous wine writer.

There are three main categories of sweet Tokaj wines:

Szamorodni: With the szamorodni, the wine clusters are picked as a whole, so a blend of regular and botrytis-infected shriveled aszú grapes make it into the wine. Hence the name szamorodni, which translates to “as it comes.” It's actually a Polish word because buyers from Poland, not far from Tokaj, were especially fond of this style of wine in the 19th century. A szamorodni is lighter, fruitier, and more approachable than an aszú and often my preferred choice. (Wines labeled "Late Harvest" are similar to a szamorodni, usually containing fewer shriveled grapes.)

Aszú: The finest expression of Tokaj's sweet wines. Winemakers soak hand-picked aszú grapes in a base wine for a couple of days to extract their flavors, then press the rich juice. What emerges after a few years in the barrel is a deeply aromatic and layered wine with signature notes of dried peach, orange, and honey. Aszús tend to get better over time, showing their most complex sides after years and even decades of aging.

Esszencia: Also known as "nectar," esszencia is the rarest type of Tokaj, made purely from the rich free-run syrup that naturally trickles from a pile of aszú berries, without the addition of a base wine. The result is a honeyed elixir with a level of concentration so high that upscale restaurants often serve it with a spoon. Rarely seen and very expensive, esszencia wines offer a playground for deep-pocketed wine collectors.

In addition to the above, fordítás and máslás are two very special types of sweet Tokaj wines, which both extract precious leftover flavors after the initial winemaking process has been completed (capitalizing on already-pressed aszú grapes and remaining lees, respectively). My experience is that it is sommeliers who get most excited about these under-the-radar bottles.

Tokaj food pairing

The classic combination with sweet Tokaj wines is foie gras, blue cheese such as Roquefort and Gorgonzola, and desserts. I prefer the aszú as an appetizer or a post-meal treat on its own. It can also go well with spicier dishes and seafood. Play around and see what does and doesn't work for you.

Visiting Tokaj

Once in Hungary, you should consider a visit to Tokaj. It's a thrillingly beautiful wine region and there's an increasing number of things to do, with a solid lineup of restaurants and hotels (and winemakers, of course).

Fröccs culture

The old tradition of mixing wine and water has disappeared in most parts of the world, but not so in Hungary, where fröccs is the name of the local water-and-wine combo. A fröccs consists of a fresh rosé or white wine and sparkling water; traditionally, people have used a siphon dispenser to add the carbonated water and hence the drink's name ("fröccsen" means to "splash" in Hungarian). Thanks to its hydrating effect, fröccs is a popular summer drink, consumed at homes, cafés, and bars.

The classic fröccs calls for two parts wine and one part water, but many combinations have sprouted, ranging from light (sport fröccs: one part wine, four parts water) to near-deadly versions (Krúdy-fröccs: nine parts wine, one part water).

My content is free and independent. If you've enjoyed this article, please consider supporting me by making a one-time payment (PayPal, Venmo).

If you're in Budapest, be sure to check out some of the city's top wine bars.