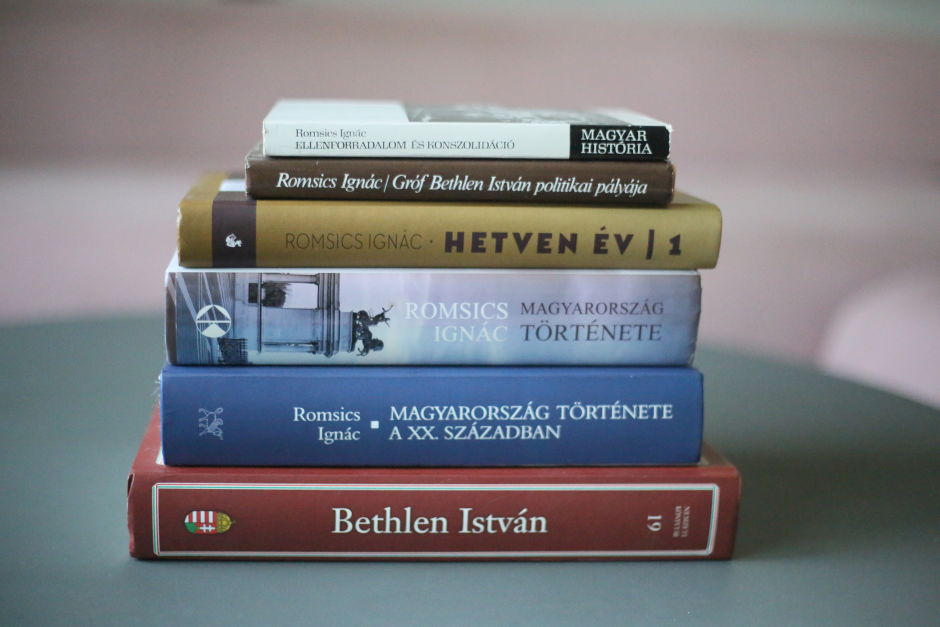

Ignác Romsics is one of the best-known historians in Hungary, specializing in the 20th century. Over his career, he has written more than a dozen books, including the ambitious monograph, Hungary in the twentieth century. Like many people from my generation who experienced only the last vestiges of Communist Hungary, my concept of the 1945-1990 period is mainly based on family anecdotes that are subjective by nature. Recently, Professor Romsics was kind enough to answer some of my questions.

Following World War II, was there any chance of Hungary not becoming a satellite state of the Soviet Union?

Not by the end of the war. If the landing of the Allies had taken place through the Balkans, as Churchill had imagined it, instead through Normandy, then it would have been possible. Or if the Italian campaign of 1943 hadn’t stalled and the Allied forces had reached Transdanubia (Western Hungary) through what’s Slovenia today by the summer or fall of 1944. This was what Admiral Mikós Horthy, Hungary’s head of state, and the Hungarian military leadership hoped for, and the reason they entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Western Allies in September of 1943.

But instead of the British-American forces, the Red Army invaded Hungary. This was in large part because on August 23, 1944, Romania declared a ceasefire and switched to the Allied side. [This cleared the way for the Soviet troops to march into Hungary from the east – TT].

This basically determined Hungary’s fate, as was evidenced by the so-called Percentages Agreement of October 1944, where Churchill and Stalin divided Eastern European countries into spheres of influence. Here, Hungary was assigned a Soviet control of 80 percent.

Many people view the Communist era as an unchanging whole, but it was more layered than that. What were the main phases of these nearly five decades?

Since the Soviet army was stationed in Hungary between 1945 and 1990, it’s not a stretch to say that we were an occupied country, one ultimately controlled by Moscow. Our sovereignty was always limited, but the level of control, and hence Hungary’s breathing room, varied throughout the period. The history of this nearly half-a-century can be divided into four distinct phases.

What were these phases?

The first one was the years immediately after the war, from 1945 to 1949. Initially, private property and a capitalist system were maintained, and repression within politics and culture was limited. But gradually the Communist initiatives started to make themselves felt. They eliminated the multi-party system and monopolized power; they nationalized private property and centralized the economy; they replaced the ruling elite and introduced a system of extreme egalitarianism but also oppression; they aggressively spread Marxist ideology within the arts.

This process was completed in 1949 with the approval of a Soviet-style constitution and the first one-party election. Between 1949 and 1956, Hungary had absolutely no independence. Every aspect of life was governed by the Communist Party, which implemented a system of terror in which people lived in constant fear.

This was the system against which people in Hungary revolted in 1956.

Correct. The Revolution of 1956 can be considered the third phase. Even though it was crushed after two weeks, the uprising proved to be a pivotal point for Hungary’s later history. It taught Hungarians its political realities and that they can’t rely on meaningful help from the outside in their fight for independence. To Moscow, it taught that Hungarians won’t put up with the type of oppression that people in the Soviet Union were subjected to.

It was this mutual revelation that yielded the pragmatic political system of General Secretary János Kádár, which has come to be known as the “Hungarian model.” It was a system that didn’t threaten the party-state and the imperial interests of the Soviet Union, but one that created conditions that most Hungarians accepted as an optimum (even if few people actually liked).

How should we picture post-1956 life in Hungary under General Secretary János Kádár?

Even the Kádár-era, which ended in 1988, can be split into two. The first one, until 1962-63, consisted of a bloody crackdown against the freedom fighters and the restoration of the state-run dictatorship. It became clear that the goals of 1956 – independence and democracy – were not happening, but also that there was no way back to the pre-1956 Stalinist policies.

What followed for the next 25 years was a softening of power into a kind of authoritarian system. Society as a whole gained some independence. The state-run economy was rationalized with capitalist elements, the dominance of the Marxist ideology ceased, everyday life was depoliticized, and the Party focused on increasing living standards. Of course, the one-party system and Hungary’s membership in the Soviet military alliance (Warsaw Pact) ensured that it wouldn’t steer too far from Soviet control.

Communism is inherently anti-religion. Were people allowed to attend church services? Was there any teaching of religion in public schools?

The ideological dominance of the church ended by 1948-49. Religious schools were nationalized and the mandatory teaching of religion ceased. By 1950, the Catholic Church had only eight (down from nearly two hundred), the Calvinist Church five, and the Lutheran and the Jewish Churches only a single high school in the country. These institutions were able to carry on, but beyond them, it was up to the courage of the parents whether their children received any religious education. If they did, this usually had to take place outside the school.

In the small Catholic village where I grew up in the early 1960s, almost every child took courses in religion (except for the Party Secretary’s daughter), and almost everyone attended Sunday services.

To what extent was Hungary’s well-being dependent on financial support from the Soviet Union?

This is a tough question, because neither of the two countries had a market economy. Prices and exchange rates were determined artificially, and the statistics we have are unreliable. Economic historians today believe that after the war and up to the 1960, the Soviet Union brutally exploited the economies of the countries within the Eastern Bloc, including that of Hungary.

After Stalin’s 1953 death this skewed system started to reverse itself, being increasingly less favorable to the Soviet Union. The main reason was that the Soviet Union exported energy very cheaply to Eastern Europe, but imported massive amounts of low-quality products almost indiscriminately. Imports to the Soviet Union from Eastern Europe almost doubled between 1975 and 1990, while Soviet exports grew at a much slower pace.

After the collapse of the regime, Hungary had a price to pay for this: its products were so inferior that they were nearly unsellable on the Western markets.

It’s often claimed that Hungary was the “happiest barrack” in the Soviet camp. Why did Hungary have it better than say Czechoslovakia or Poland?

As mentioned above: because of 1956 and the policies of General Secretary János Kádár.

Did the Communist period yield any positive results?

Providing for everyone, especially in terms of food, was very important to the Kádár regime. It was in this period, between 1960 and 1980, that big chunks of Hungarian society could for the first time live their lives without experiencing periods of starvation. The consumption of meat, sugar, eggs, dairy, and fruits all multiplied. Hence the name of this period: “goulash communism.”

Living conditions also improved. People lived in less crowded apartments that had more amenities than ever before, such as bathrooms and refrigerators (in 1949, only 10 percent of apartments in Hungary had a bathroom, by 1990, the rate was nearly 80 percent). This is why Kádár’s era is also known as “frigidaire socialism.”

Social security covered nearly everyone by the 1960s and healthcare was practically free. Real incomes between 1950 and 1990 almost quadrupled, while inequalities were extremely low (the income difference between the top and the bottom ten percent of society was only 4-5 times in the 1980s).

Some movies of the late ‘60s were subtly critical of the regime. To what extent were the arts censored by the Party after 1956?

The Kádár era brought an improvement within culture, too, although freedom of the arts was far from complete. In exchange for respecting certain taboo subjects such as the 1956 Revolution, the lack of a multi-party system, and the role of the Soviet Union, artists were relatively unconstrained to pursue their own creative paths.

The Party Congress of 1966 determined that (i) they’ll support artworks that reach the masses and are socially-minded, (ii) permit artworks that are politically not hostile, and (iii) ban those that are openly critical. This came to be known as the famous cultural system of the three “Ts” – supported, tolerated, and banned (“támogatott, tűrt, tiltott” in Hungarian).

How is the post-1956 Communist regime viewed today?

It changes. There was a fall in living standards in the years immediately after the collapse of the Communist regime in 1989, which meant that many people were disillusioned by the capitalist system. Most unhappy were low-skilled and agricultural workers, who noticed the widening gap between them and those who benefited from the new world, which were corporate managers and intellectuals.

As the living standards increased by the late 1990s, the nostalgia for the Kádár-regime faded and there was more hope for the future and for democracy. Still, as late as 1999, 40 percent of Hungarians viewed János Kádár the most likable politician of the past century. My guess is this number is lower these days.

The first volume of your memoir – “Seventy Years” – was published recently. As a young man, you were a voracious reader of novels and an avid moviegoer. Can you share your favorite books?

The two most recent books that absorbed me were Hollóidő (2001) by István Szilágyi and Koppantó (1979) by Zsolt Mester. Both of them by writers from Transylvania. Hollóidő is seemingly about Transylvania’s early-modern history, but indeed it deals with the moral and political dilemmas of our times. Koppantó is about the life of a landed family in the Szilágyság region between the world wars and the family’s collapse after the war.

How about films?

As a child, I loved films about the Soviet partisans. In my twenties, I was a fan of director Miklós Jancsó and later that of István Szabó. I especially liked Szabó’s Sunshine (A napfény íze), and of course his movies from the ‘80s such as Mephisto and Colonel Redl (Redl ezredes). The Door (Az ajtó), directed by Szabó in 2012, presents an impressive range of emotional registers.

But if I had to choose a favorite, I’d go with the movies of Andrzej Wajda, especially those from the 1970s, such as Landscape After the Battle (Tájkép csata után), The Wedding (Menyegző), and The Promised Land (Az ígéret földje). Katyn, too, was good, but a bit too didactic to my taste – I thought the portrayal of the collaborators was one-dimensional.

Wajda’s films were almost always about one thing: Polish history. I regret that we don’t have a comparable director. We don’t even have a movie about the Treaty of Trianon, about which we talk so much. And none about the Battle of Mohács nor that of the Don Bend.