Answers to all your questions about Hungary's most famous wine and its region.

What is Tokaj and what happens there?

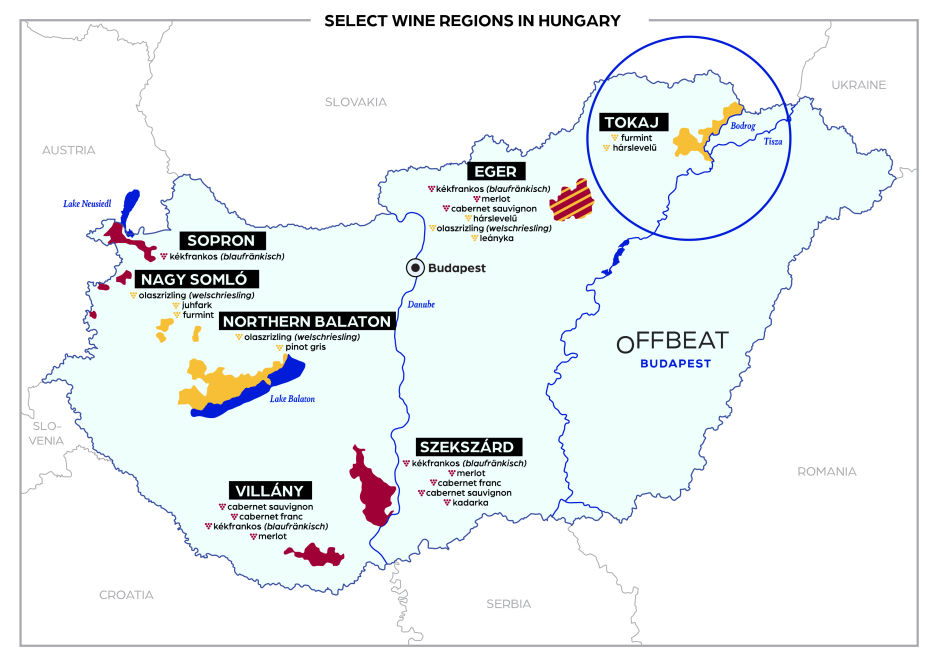

Tokaj, officially the “Tokaj foothills” and occasionally spelled “Tokay,” is Hungary's most famous wine region, located in the northeastern part of the country. The town of Tokaj has come to represent the whole wine region, but the area spans 27 villages, 5,400 hectares (13,000 acres) of planted vines, and hundreds of mostly small wineries.

Click here to expand the wine map.

A Unesco World Heritage Site, Tokaj has long been known for its golden-hued wines made naturally sweet by the work of a benign fungus. It was Louis XIV, the King of France, who famously said that Tokaj was “the wine of kings, the king of wines.” Today, both sweet and dry wines are made here.

What are Tokaj’s sweet wines?

Before you close your browser upon seeing the words "sweet wines," let me assure you that these wines are different from what you might be thinking of. They aren't made with added sugar, for example. Instead, winemakers take advantage of the work of a much-desired fungus called botrytis, which can attack some of the grapes. While the fungi munch away, a range of new aroma compounds are created — peach, honeycomb, orange are most typical.

When they're done feasting, the fungi leave behind shriveled berries with a concentrated sweet-tart flavor. Grapes infected by this “noble rot” are called aszú, and aszú wines are the heart of Tokaj’s sweet wines. The climatic conditions don’t align every year, meaning that a sweet wine vintage in Tokaj is always precious and never guaranteed.

Despite being sweet, these wines aren't cloying because their acidity offsets the sweetness. "Sweetness so balanced and held in check by the sharp-tasting furmint grape that they leave your mouth whistle-clean,” wrote Hugh Johnson, the famous wine critic.

What's special about the climate and soil of Tokaj?

There's a unique microclimate in Tokaj that provides the ideal conditions for winemakers to capitalize on the botrytis fungus. First, Tokaj's many rivers and streams provide sufficient humidity to attract the fungus. In fact, two major rivers, the Bodrog and the Tisza, join together right outside the town of Tokaj. Second, the long and dry falls help the fungus-affected grapes to dry out and concentrate.

Tokaj is a cool-climate wine region that sits on the remains of hundreds of volcanic eruptions. The bedrock mainly consists of rhyolite and andesite with a mineral-rich clay topsoil, yielding wines that can be notoriously concentrated and minerally. One exception is the area around Tokaj and Tarcal, where the loess topsoil – accumulation of windblown sediments from the nearby Hungarian Plain – translates to more subtle and delicate wines.

The exact soil composition and hence the resulting wines can be very different across the vineyards, even between neighboring parcels. To highlight this diverse terroir, many wineries produce single-vineyard wines.

What should I know about the history of Tokaj wines?

Unlike with the Roman-planted vineyards in western Hungary, it's unlikely that the Hungarian tribes found any grapes when they invaded Tokaj in the 9th century CE. French, German, and Italian settlers in the 12-13th centuries helped improve winemaking with new techniques like soil management, pruning, and barrel aging. In fact, some of the village names in Tokaj still bear witness to these newcomers, for example Tállya, which comes from Old French, and Bodrogolaszi, which translates to "Italians by Bodrog."

Tokaj's rise in the 16th century was prompted by Ottoman Turkey's occupation of southern Hungary. Szerémség, which had been the top wine region, became part of the Ottoman territories and lost it relevance. Tokaj remained free and turned into the new winemaking center as vintners from other parts of the country flocked there.

During its golden age in the 17-19th centuries, Tokaj's specially made sweet wines were a status symbol across royal courts and the European aristocracy. The Russian tzars maintained a dedicated purchasing committee in Tokaj throughout the 18th century (hence the Russian orthodox church, which still stands in Tokaj's downtown). But with the partitions of Poland, also a major market, the punitive tarrifs introduced by Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa to support Austrian over Hungarian wines, and the shifting global tastes from sweet to dry wines, things started to look less rosy for Tokaj.

For much of Tokaj's history, feudal aristocrats owned the vast vineyards. Most notable was the Rákóczi family, which lost it all in 1711 when Ferenc Rákóczi II led an unsuccessful war of independence against the Habsburgs. After this, families loyal to the Habsburg court, such as the Trautsons and the Degenfelds, became the major landlords.

Tragically, the Europe-wide phylloxera bug, which appeared in Tokaj in 1885, destroyed most vineyards. Desperate winemakers who suddenly lost their livelihoods migrated to the United States en masse. It took a hundred years for the wine region to get back to pre-phylloxera production levels. After the Austro Hungarian Empire collapsed in WWI, two of Tokaj’s twenty-nine villages were annexed to newly created Czechoslovakia (today, they’re part of Slovakia).

During the Communist era (1948-1989), the Hungarian state nationalized the vineyards and the state-owned cooperatives churned out mediocre wines in mass quantities. They planted new vineyards on easily accessible but low-lying sites. The biggest market became the Soviet Union, with a seemingly unquenchable thirst for wines. The onset of capitalism ushered in prominent international wineries who, together with local family producers, began the long process of restoring Tokaj's prestige.

What kind of grapes grow in Tokaj?

Synonymous with Tokaj are furmint and hárslevelű, two white grapes native to Hungary that together acccount for nearly 90 percent of all planted vines. What made them so widespread in Tokaj is their ability to ripen around the same time and to attract the benign botrytis fungus, the noble rot, a key component in sweet aszú wines. Today, furmint and hárslevelű grapes are used for everything from dry wines to sweet wines, from single varietals to blends.

Accounting for two-thirds of the total, furmint is Tokaj’s main grape. With a racy acidity, furmint makes crisp, elegant wines, while also reflecting Tokaj’s volcanic soil with a mineral tingle. In sweet wines, furmint’s high acidity is essential in keeping sweetness in check. The more aromatic hárslevelű can take the edge off furmint in blends and round out the wines.

The endearingly aromatic Muscat blanc à petit grains (sárgamuskotály) occasionally also appears in blends. Three addition grapes are officially permitted to grow in Tokaj – zéta, kabar, kövérszőlő – but they're negligible.

What makes Tokaj wines sweet?

In general, a wine is sweet when the fruit sugars in the grapes don't fully ferment into alcohol. In Tokaj, the botrytis fungus concentrates the contents of the grapes, including their fruit sugars, and the grapes are harvested with much higher fruit sugar levels than those in regular wine regions. Some of those sugars don't transform into alcohol during the fermentation process, instead remaining in the wines as so-called residual sugar. Apart from being delicious, residual sugars balance out the inflated acidity levels in the wines.

How much sugar do Tokaj's sweet wines contain?

Less than most people think. Plenty of cocktails and even a can of coke contain more sugar than many Tokaj wines. The "sweet wine" label is somewhat misleading: Yes, these wines are sweet, but not that sweet; what makes them special is their complex aromas, layers of flavor, and a balance between the sweetness and the acidity.

Do people drink sweet wines?

Many do, including lots of sommeliers and myself. Tokaj's sweet wines are delicious and versatile (see more below on food pairing). Wineries since the early 2000s have shifted to making fresher, fruit-forward, more approachable sweet wines. They keep the sugar levels under control so that the grapes, the soil, the botrytis-induced flavors can express themselves. A 2013 wine law aligned these updated consumer preferences with the official critieria.

Why is acidity so important with Tokaj wines?

Because acidity offsets the sweetness and prevents these wines from tasting cloying. Furmint, Tokaj's most-planted grape, is known to be naturally high in acidity, and the botrytis fungus further concentrates this acidity by drying out the grapes. The result is a unique balance between sweet and sour – a good Tokaj is always fresh and clean-tasting.

Also, good acidity levels enable a wine to be suitable for aging. This is why Tokajs, especially the sweet wines, are drinkable for decades and many show their best selves twenty or even more years after bottling.

What kind of sweet wines exist in Tokaj?

There are four main categories of sweet Tokaj wines:

Late Harvest (Késői Szüret): Wines labeled as "Late Harvest" are picked when the grapes are overripe, some of them already shriveled by the botrytis fungus. Late Harvest wines are a good foray into the world of sweet wines because they deliver some noble-rot flavors but they aren't as rich as an aszú. By law, Late Harvest wines contain at least 45 grams / liter of residual sugar.

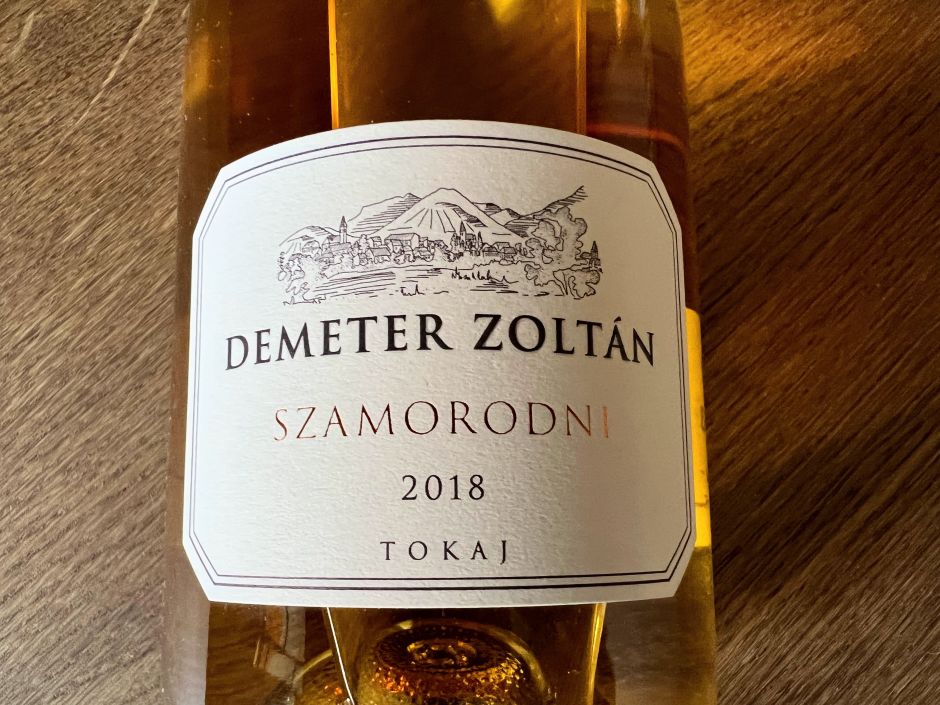

Szamorodni: With szamorodni wines, the harvested grape clusters contain some berries that have been botrytized by the fungus and some that haven't (regular grapes). The name szamorodni comes from Polish and translates to “as it comes,” referring to this mixture of regular and botrytis-infected aszú grapes that make it into the wine. Why Polish? Because Poland, not far from Hungary, was an especially big export market for Tokaj wines in the 19th century.

Before the aszú became prominent in the 17th century, szamorodni was Tokaj's most important wine (it was called "the main wine" or "főbor" in Hungarian). By law, a szamorodni contains at least 45 grams / liter of residual sugar and is aged for a minimum of six months in oak barrels.

Aszú: Aszú is the finest expression of Tokaj and botrytis-made wines. The aszú evolved in the 17th century from the szamorodni, above, for reasons of commerical logic: depending on the vintage, the flavor of a szamorodni fluctuated from year to year, showing swings in sugar content for example. Since customers preferred a more predictable taste profile, Tokaj winemakers started to make wines from a fixed amount of fungus-infected shriveled grapes (aszú) each year, using a method that has effectively remained unchanged since.

Of course, these raisin-like dry grapes hardly contain enough liquid to make a wine, so winemakers soak the carefully measured, hand-picked aszú grapes in a so-called base wine for a few days (the base wine is made from regular grapes that were picked earlier in the harvest). Once the flavors of the aszú grapes have been extracted, the rich juice is pressed, fermented, and left in underground cellars. What emerges after years of barrel aging is a deeply aromatic and layered wine with signature notes of dried peach, orange, and honey. Aszú wines tend to improve over time – picking up notes of Christmas spices, coffee, tea, chocolate.

The word "puttony" appears on many aszú labels. Puttony is a wooden carrying basket used in the past for collecting and measuring aszú grapes during harvest. Depending on how many puttonyful of aszú berries were added to a 136-liter capacity so-called Gönci barrel of base wine, the resulting aszú was assigned a puttony-rating. The actual puttony, sadly, is no longer in use – instead harvesters rely on regular buckets to collect the aszús – but, using a conversion, wineries can elect to show puttony on their labels. It's not mandatory, though.

There exist five and six-puttony aszús, containing at least 120 and 150 grams per liter of residual sugar, respectively. If no "puttony" is shown on the label, the aszú wine is to contain at least 120 grams of residual sugar with a minumum 18 months of aging in oak barrels.

Esszencia: Also known as "nectar," esszencia is the rarest type of Tokaj, made purely from the rich free-run syrup that naturally trickles from a pile of aszú grapes, without the addition of a base wine. The result is a honeyed elixir with a level of concentration so high that upscale restaurants often serve it with a spoon. The esszencia's first mention is from 1707, when Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II sent it to royal courts across Europe to drum up support for his war of independence against the Habsburgs. Today, esszencia wines command top prices, offering a playground for deep-pocketed wine collectors.

In addition, there are two less common wines made after the initial processing: fordítás extracts precious leftover flavors from already-pressed aszú grapes, while máslás relies on leftover lees (with a base wine added to both). While exhibiting close to the signature flavors of an aszú, fordítás and máslás are usually somewhat cheaper. (Few wineries make fordítás and máslás these days; my experience is that it's sommeliers who get most excited about them, in part because these bottles are so rare.)

Why are Tokaj's sweet wines relatively pricey?

For three main reasons. First, harvest in Tokaj is a long, drawn-out process and hence expensive: laborers do several rounds of picking usually between October and November, in search of the shriveled grapes (not all grapes on a given bunch are hit by botrytis and not all at the same time). Second, a related point, workers need to individually pick aszú grapes off the bunch. On an average day, they may pick eight kilos (18 pounds) of aszú compared to 500 kilos (1,100 pounds) of regular healthy grapes by the cluster. Finally, they're expensive because it requires a significantly higher quantity of shriveled grapes to make the same amount of wine than with regular grapes.

How is Tokaj different from Sauternes?

Some people are more familiar with the sweet wine region of Sauternes, near Bordeaux, than Tokaj. Ironically, Tokaj has been making botrytis-induced sweet wines for a longer period of time. It's never easy to generalize, but there are some key differences.

First of all, the two wines are made from different grape varieties (furmint/hárslevelű vs. sémillon/sauvignon blanc). Second, Tokaj is more recognizable for its bracing acidity, which reduces the sensation of sweetness, while Sauternes is more known for its round, buttery mouthfeel because of the use of new oak barrels.

Does Tokaj also make dry wines?

Yes. As a reaction to shifting global tastes, Tokaj winemakers started producing dry wines starting around 2000. In fact, many wineries make more dry than sweet wines these days. There's usually a first harvest in September when they pick healthy grapes for the dry wines (the harvest for the botrytis-affected shriveled grapes takes places usually throughout October and November).

For now, there exist meaningful stylistic differences across Tokaj's dry wines. Most of them tend to be fresh, crisp, vibrant, and fruit-forward, released within a few years of harvest. But some of the leading wineries, such as Királyudvar, Royal Tokaji, Oremus, Disznókő, and Szepsy aim for a more complex expression. They harvest the grapes from their best vineyards planted with old vines, and thoughtfully age the wines in oak barrels, as with a white Burgundy. The results are textured and concentrated wines that show a promising potential for dry Tokajs.

What should I know about pezsgő, Tokaj’s sparkling wine?

With the general upswing in sparkling wine consumption, a rising number of Tokaj winemakers started to produce bubbly wines in recent years. For many, this takes the form of the fun and fashionable pet nat, where the fermenting wine is simply sealed in a bottle before it completes the fermentation and is usually popped open – with sediments and all – soon after.

To qualify for pezsgő, the official sparkling wine label, Tokaj producers need to abide by the Champagne-method (méthode traditionnelle). This means a two-step fermentation followed by disgorging, which is the removal of lees, to achieve a clean-looking sparkling wine. There are also requirements for bottle aging (nine months) and grape varieties (the same six used for dry wines). The honor of making Tokaj’s first-ever pezsgő belongs to Királyudvar (2007 vintage).

The most dedicated producers make their pezsgő in-house. Besides Királyudvar, Zoltán Demeter, Sauska, Pelle, and Tokaj Nobilis are usually regarded as the leading labels. With the exception of Sauska, which makes more than a quarter million bottles of pezsgő each year from a mix of purchased and grown grapes, these are small-scale, “grower pezsgő” operations, often bottling from single vineyards and releasing vintage bottles.

What kind of food goes with Tokaj wines?

The classic combination with sweet wines is foie gras, blue cheese such as Roquefort, Stilton, and Gorgonzola, and desserts. I prefer my sweet Tokaj either as an aperitif, or as a post-meal treat on its own, in place of or after a dessert. Lately, I've also been enjoying aszús and szamorodnis with spicy dishes, Thai curries for example, where the richness and acidity of the wines cut through the sharp flavors.

Dry Tokajs work well with salads, fish, and roast pork. Using the furmint grape's acidity, these wines pair nicely with any dish that could use a squeeze of lemon juice. (Find out how a leading New York sommelier pairs his Tokajs).

What are the best vineyards of Tokaj? Is there a classification system like in Bordeaux or Burgundy?

In 1737, a royal decree laid out the 22 villages that were permitted to using the Tokaj name, creating the first closed wine region in the world. Around the same time, a total of 231 Tokaj vineyards earned a first, second, or third class designation. Most of the 48 first-class parcels were in the villages of Tarcal (14), Tállya (8), Tokaj (7), and Mád (6). In 2012, local winemaker László Alkonyi updated Tokaj’s centuries-old classification system.

Who owns the wineries in Tokaj?

After the fall of Communism, the Hungarian state began to privatize Tokaj’s state-owned vineyards in the 1990s. This resulted in a handful of cash-rich foreign companies acquiring massive holdings. For example, Vega Sicilia, the iconic Spanish winery, owns Oremus; AXA Millésimes, the French wine conglomerate, owns Disznókő; and Anthony Hwang, an American investor also in charge of Domaine Huet in the Loire Valley, owns Királyudvar. In terms of size, they are followed by a few large Hungarian-owned family wineries such as Szepsy and Sauska. Finally, there are also hundreds of small family wineries in Tokaj with a few hectares of plot each.

Most winemakers in Tokaj agree that foreign companies were essential in putting Tokaj back on the international wine map by bringing much-needed capital, technical expertise, and a global distribution network. Hugh Johnson, the British wine writer and author of “The World Atlas of Wine,” was an early proponent of Tokaj and later a minority shareholder of Royal Tokaji, one of the big producers.

Today, the Hungarian state has one remaining holding, Grand Tokaj, which produces wines mainly from grapes purchased from mom-and-pop winegrowers. More recently, big-pocketed Hungarian businessmen like József Váradi, the CEO of Wizz Air, were also lured by the siren song of Tokaj, acquiring wineries as side projects.

Who are the leading winemakers?

Depends who you ask. I've been regularly visiting the wine region for the past five years, meeting winemakers and tasting their wines, and based on my impressions, these are the leading producers currently. Of course, this is a personal view, and others may disagree with me.

Do Tokaj wineries practice organic farming?

Since Tokaj is a humid wine region, it's harder for local winemakers to protect the grapes from naturally occuring molds and fungi than for wineries in drier regions (this humidity draws also the desirable botrytis fungus). As a result, few Tokaj producers are able to farm fully organically, without the use of pesticides (notable exceptions include Királyudvar and Hétszőlő). Many wineries, however, practice sustainable agriculture.

Are there natural and orange wines in Tokaj?

Several wineries have started to experiment with natural wines and other contemporary products, such as the bubbly pét-nat. Dorka Homoky and Szóló, both of them small family wineries in the village of Tállya, put out unfiltered, unclarified dry furmint wines made with only a very small amount of added sulfites.

Is Tokaj worth visiting?

Absolutely. Despite a long history of winemaking, Tokaj isn’t nearly as popular as other historic wine regions like Bordeaux or Burgundy. Part of this is because Tokaj was hidden behind the Iron Curtain for decades, away from the Western world. But in the post-Communism present, this also means it has retained an unmistakable sense of place and it’s more approachable than tourist-heavy wine regions.

If it wasn’t for the occasional state-of-the-art wineries that stand out from their surroundings, you’d think that time has stopped long ago in Tokaj. Softly rolling hills coated in vineyards connect Tokaj’s sleepy medieval villages, some of them tucked away in green valleys with less than a thousand residents. The pace of life is slow, visitors are few. You can feel as if you have the area all to yourself: A few birds of prey gliding above are the only creatures you’ll have to share the sunset vistas with from the top of Szent Tamás vineyard.

The wine tastings, too, are more personal than what you might be used to. At many of the smaller wineries it’s the head winemaker who leads the tastings, especially if you book in advance. You can ask her or him about anything: approach to winemaking, favorite vintage, visions for Tokaj.

Is there anything to do in Tokaj besides wine-tasting?

Although mainly a wine region, not everything is about fermented grape juice in Tokaj. Cradled by the Zemplén mountains, the area is beautiful and rich in panoramic hiking trails. There are also a couple of excellent restaurants, a medieval church in almost every village, a renaissance castle in Sárospatak, and a rich Jewish history throughout the region. Also, several accommodation options offer a chance to experience the once-lavish lifestyle of the Hungarian aristocracy. See my specific recommendations here.

What should I know about Tokaj's Jewish history?

As wine merchants, Jewish people played a key role in selling Tokaj wines across Europe. Despite the local laws that made it hard for them to ply their trade, by the 19th century Jews were in charge of most exports. They introduced a much-needed spirit of capitalism into the antiquated system of distribution overseen by feudal landlords.

In many towns, the Jewish population reached twenty percent, with Mád, Tolcsva, Abaújszántó, and Sátoraljaújhely being the centers (the Baroque synagogue of Mád was nicely refurbished recently). Tragically, almost all of Tokaj's Jews were deported to Auschwitz in 1944 and killed in the Holocaust. The few survivors soon left Hungary.

This part of northeastern Hungary was a hotbed of the ultra-orthodox Hasidim. As a poignant reminder of Tokaj's once flourishing Jewish life, every year, big groups of Hasidic Jews from New York City descend on the village of Bodrogkeresztúr (Kerestir in Yiddish) and Olaszliszka (Liska) to commemorate the death anniversary of the legendary rebbes who lived here.

What’s the best way to get into and around Tokaj?

The Tokaj wine region is located 230 kilometers (145 miles) from Budapest. By car, travel takes about two and a half hours to get to its southernmost end. There’s also a direct, three-hour train service between Budapest’s Keleti railway station and the town of Tokaj, but I highly recommend you take a car.

The wine region consists of 27 villages, but Tokaj, Tarcal, Mád, Erdőbénye, and Tállya have the highest concentration of renowned wineries (Tokaj and Sárospatak, a city in the north, are the most cultural). The settlements are usually within less than ten minutes from one another by car. There’s just a single taxi company in the whole wine region and hence a cab isn't available at all times. (If you decide to use a taxi, it costs around €15 to travel from one village to the next, and the cab company, Pirint Taxi, is reachable at +36 30 958 7495.)

Can I buy wines in Tokaj?

Yes. After the tastings, there’s a chance to purchase wines directly from the wineries at prices that are meaningfully cheaper – between €10 and €30 for most bottles – than what you might have paid for Tokajs in wine shops or restaurants in the past.

What else should I be mindful of before visiting Tokaj?

Just remember that the Tokaj wine regions consists mainly of small villages, with up to a couple of thousand residents in each so as night falls, the streets become eerily quiet. But don’t despair. I recommend many tried-and-tested wineries, restaurants, hotels, and activities, and also remember that a sense of discovery can be part of the fun of traveling.

My content is free and independent. If you've enjoyed this article, please consider supporting me by making a one-time payment (PayPal, Venmo).