What this panoramic wine region lacks in international renown, it makes up for in sheer beauty and a colorful cast of family wineries.

What is the northern Balaton wine region and what happens there?

Located in western Hungary an hour from Budapest by car, the 77-km (48-mile) long Balaton is Central Europe’s biggest lake. The lake's northern side is a top wine region and one of the great natural treasures of Hungary. Teeming with panoramic valleys, volcanic hills, and medieval villages, this bucolic countryside has had a thriving wine culture since the Romans. Unfortunately, the last century transformed Balaton into a summer holiday destination and spoiled some of its native beauty, but still, there are many gems left to explore here.

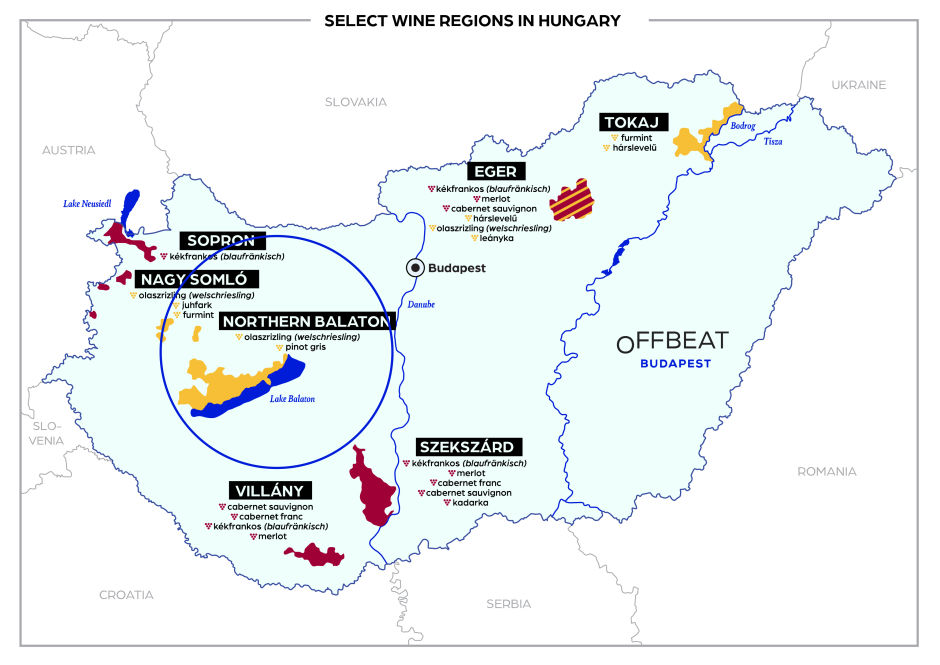

Click here to expand the wine map.

Grapevines also grow on the south side of Balaton, but this guide covers only the north, which has a total of 3,500 hectares (8,650 acres) of planted vines and it officially consists of three different wine regions — Balatonfüred-Csopak, Badacsony, and Balaton Felvidék. I will treat them as one, which is how they were in the past, with a focus on the first two subregions.

What should I know about the history of Balaton wines?

Balaton was part of the Roman Pannonia Province from the 1st century AD, and the excavated agricultural estates — villa rusticas — show a thriving winemaking culture around the lake (except for the short period when Emperor Domitian tried to limit competition to Italian wines). Hungarian tribes, who took the land in the 9th century, continued to make wine, as did the Avar and Slavic people before them. The Ottoman occupation of Hungary in the 16th century caused a major disruption as Balaton turned into a battle zone, years went by without a harvest, and the population declined. This was when new winemaking centers formed in the unoccupied northern Hungary, in Tokaj for example. The revival came in the 18th and 19th centuries, when Habsburg Austria grew fond of Balaton wines and purchased mass quantities.

The Europe-wide phylloxera epidemic appeared in 1879 and gradually destroyed 65 percent of the vineyards. Having suddenly lost their livelihoods, many Balaton winemakers emigrated to the United States. This was also when the first waterfront plots were sold to vacationers, beginning Balaton’s slow but steady transformation from wine country to summer resort.

During the Communist period, especially from 1959, state-owned cooperatives planted new vineyards on low-lying (and lower quality) sites that could be cultivated by machines. In the meantime, many family winemakers abandoned their hillside plots in the face of economic and political headwinds. The result was mediocre wines in mass quantities. From 1992, the capitalist era brought a revival of small, private wineries that are currently the main pillar of the region.

How does the wine region co-exist with Balaton's tourism?

With the advent of widespread car ownership and the completion of the M7 highway from Budapest, tourism to Balaton has skyrocketed since the 1960s. What were once quiet hills blanketed in vineyards have turned into busy vacation towns overbuilt with summer homes of questionable taste. Many people rightfully bemoan the resortification of Balaton, believing that it caused irreparable harm to the pristine environment. While this is true, there still exists unspoiled nature a bit away from the lake, further inland, which is also where many of the wineries are located (this guide will help you find them). And there’s also a benefit to high-traffic tourism: Balaton offers significantly better food and accommodation options than other Hungarian wine regions.

What kinds of wines are made in Balaton?

Balaton is a white wine region. Many of the native grapes — fehér gohér, sárfehér, kolontár — disappeared in the 19th century, when vintners replaced them with foreign varieties that were considered to be better; this was when olaszrizling (welschriesling) became widespread. Accounting for 40 percent, olaszrizling is by far the most common grape across northern Balaton today followed by pinot gris with 10 percent. There's also a small amount of red grapes, especially kékfrankos (blaufränkisch) and cabernet sauvignon.

What should I know about olaszrizling, Balaton’s most planted grape?

Despite a relatively short history in Hungary — it was first planted in the early 19th century — olaszrizling (welschriesling) has become synonymous with the northern Balaton wine region. Olaszrizling is unrelated to the better-known riesling from the Rhine region, instead originating in France but finding its true home in Central Europe: besides Hungary, it’s also common in Austria, and Croatia, where it’s called grasevina. It’s a reliable and frost-resistant grape with good acidity, floral and peachy aromas, and a flavor reminiscent of bitter almonds. The mass-produced stuff of the Communist era tarnished olaszrizling’s reputation for decades, but Balaton winemakers are once again putting out wonderful bottles. Especially renowned is the olaszrizling of Csopak.

This wine region is massive! What are the central points to visit?

It’s not as massive as it seems: it takes about an hour to drive from one end to the other. Having said that, the area around Csopak, nearer to Budapest, and Badacsony, on the other end, are the two central attractions for wine lovers. Csopak is regarded as the heart of olaszrizling, while the volcanic hills of Badacsony make their own, separate and distinct minerally wines. The inland landscape between Csopak and Badacsony is strikingly beautiful. There are softly rolling hills peppered with old villages and soaring church towers as far as the eye can see.

My content is free and independent. If you've enjoyed this article, please consider supporting me by making a one-time payment (PayPal, Venmo).

What should I know about Csopak and its wines?

Being nearer to Budapest and right next to the city of Balatonfüred, Csopak is usually busier and has more vacationers than Badacsony. The dominant grape is olaszrizling, in fact, Csopak is the only wine region in Hungary where a region denotes a specific grape type. For a wine to qualify for the top “Csopak” label, it has to meet strict requirements as stipulated by the “Csopaki Kódex,” which governs everything from specific vineyards to minimum planting density and maximum yield. Two of the top wineries in all of Hungary, Figula and Jásdi, are based here and well worth visiting.

The restaurant options are many and diverse, more so than in Badacsony, but it's also true that Csopak has gotten very expensive by local standards as rich vacationers from Budapest push up the prices. For a change of pace, I highly recommend you drive through the adorable nearby villages of Balatonszőlős, Pécsely, Vászoly, and Dörgicse, where thatched roofs and kitchen gardens are still the norm rather than the exception.

What should I know about Badacsony and its wines?

Badacsony is situated on the far end of Lake Balaton from Budapest and takes about two hours to reach by car. There’s a truly unique landscape here: half a dozen volcanic hills near one another spring out of the flat terrain; with the lake as the backdrop, they’re a dramatic sight to behold.

Badacsony and Szent-György hills are the biggest and with the most wineries and restaurants. While parts of Badacsony Hill can feel a little touristy, Szent-György Hill draws fewer people and it’s also where many of the top producers are based. The local wines tend to have a minerally tinge, and while olaszrizling is most common, native grapes like kéknyelű and budai zöld are making a comeback.

If you have some free time, it’s worth driving through the charming villages of the neighboring Káli-medence, especially Köveskál, Kővágóörs, and Kékkút, which have excellent though pricey restaurants that cater to Budapest vacationers.

Who owns the wineries in Balaton?

Unlike in other parts of Hungary where many feudal landlords owned the vineyards, local farmers with small plots were common in Balaton. Their cute winery buildings with gleaming-white walls and thatched roofs are still scattered throughout the region. (The renowned 19th-century Csopak winery of János Ranolder, the Archbishop of Veszprém, and the Dörgicse winery of the Piarist Order were notable exceptions.)

A post-WWII land reform confiscated all sizable vineyards. By 1960, the majority of them belonged to state-run cooperatives. Small family wineries reappeared after the privatizations of 1992, and today, apart from a few large producers like Varga and Laposa, they’re once again the backbone of Balaton winemaking.

What’s the soil composition of the Balaton vineyards?

It varies. The topsoils around Csopak are rich in marl (a mixture of clay and limestone), which helps with nutrient uptake, acidity, and water retention. In eastern Csopak, the recognizably reddish color comes from disintegrated sandstone high in iron oxide deposits. The heftiest and most minerally wines tend to come from the volcanic hills of Badacsony — Badacsony, Szent-György, Gulács, Tóti, Csobánc, Szigliget — that are overlaid with a basalt crust and strewn with solidified volcanic ash called tuff.

Balaton itself affects the vineyards situated along its shore by reflecting the sun’s rays, which accelerates the ripening of the lake-facing grapes (with a warming climate, this isn’t necessarily a good thing).

Is the wine region worth visiting?

Absolutely. Sure, Balaton doesn’t have the international renown of Tokaj, but it makes up for it in sheer beauty and a colorful cast of winemakers. Before a visit, keep in mind Balaton's highly seasonal nature: while places can get packed in the summer, they're often deserted before April and after October. This doesn’t mean that a late-fall visit is off the table, just be sure to plan and book ahead because some of the restaurants and wineries close down in the off-season.

What's the best way to get into and around the wine region?

Csopak is about an hour, Badacsony a two-hour drive from Budapest. Having a car is indispensable and it also allows you to explore the adorable medieval villages scattered throughout the region, for example Balatonszőlős, Pécsely, Vászoly, Dörgicse, Köveskál, and Kővágóörs.

My content is free and independent. If you've enjoyed this article, please consider supporting me by making a one-time payment (PayPal, Venmo).

Which wineries should I visit?

It depends. First, decide whether Csopak or Badacsony has more appeal to you and then skim through these winemaker profiles to get a sense for what’s special about them. Some are small family wineries, others bigger operations, but they each have a unique approach to winemaking.