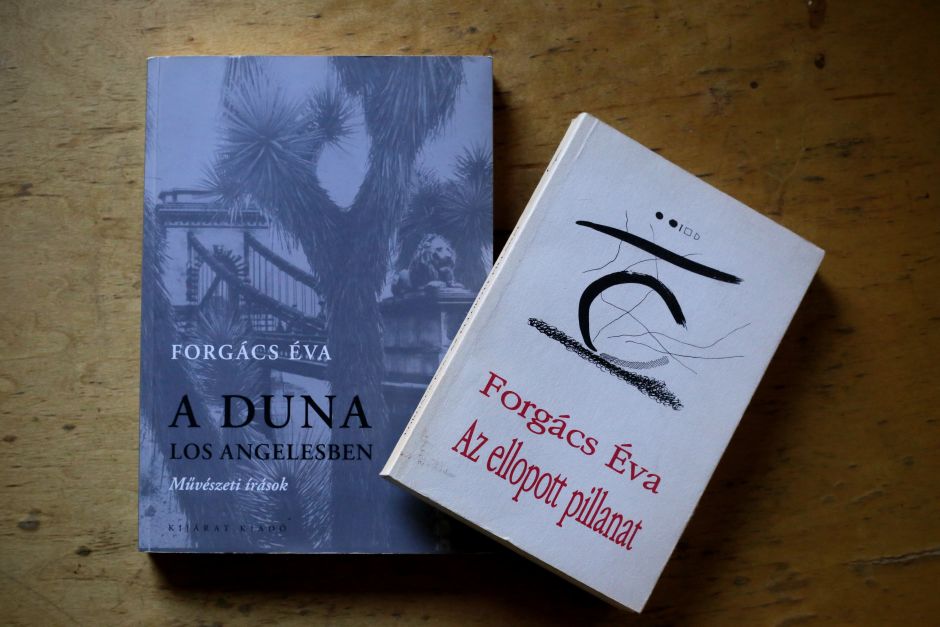

Éva Forgács is an art historian who teaches at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena California. Before moving to the United States, she was a teacher at the Moholy-Nagy Művészeti Egyetem. She has published numerous books and articles about art in Central Europe, with a particular focus on the avant-garde period. Recently, Éva and I spoke about the history of painting in Hungary, touching upon the key milestones between the 19th century and the present day. Below, you can read our conversation, which has been lightly edited for length.

Painting in Hungary doesn’t go back very far. Why is that?

For reasons of history. In Holland, for example, painting was part of daily life for the middle classes since the 17th century. In Paris, going to the Fall Salon was like attending a fashion show, expecting new art that could be purchased. It was a public affair. Hungary didn’t have an urban population until the middle of the 19th century.

This means that many of the Western art movements never appeared in Hungary.

Yes. There wasn’t much of an Enlightenment movement, so there was no passionate Romanticism to battle it either, certainly not the kind associated with Rousseau in France and the romantic painting and literature in Germany. As a result, there could be no Realism to confront it.

Were there any exceptions?

There was László Mednyánszky’s brand of contemplative Romanticism, and the plein-air painting of Pál Szinyei Merse.

At which point did painting in Hungary come into its own?

With the founding of the Nagybánya art colony in 1896. This group was informed about European impressionism and painted a distinct local variant of it. For those interested, Károly Ferenczy’s paintings at the National Gallery in Budapest is a good place to start. Also, Nagybánya was the basis of many important art movements that came later.

Including the Nyolcak (The Eight; founded in 1909), which is probably the most prominent.

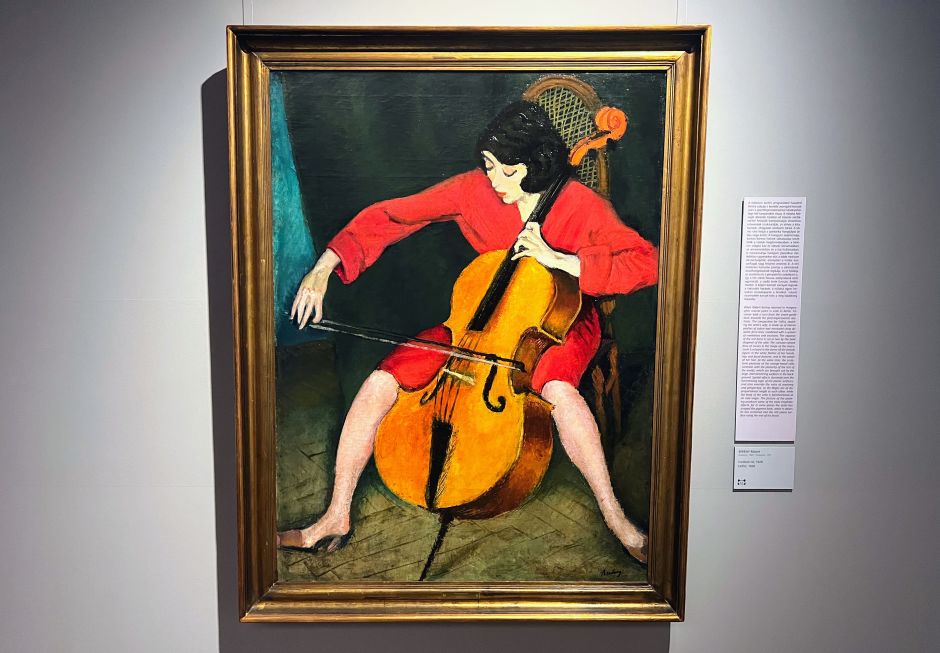

The Nyolcak consisted of a mixed group of eight artists who were influenced to different degrees by Cezanne, by Cubism, by the Fauves, and by Expressionism. Its radical wing included the brilliant and rebellious Róbert Berény, who favored a version of expressionist style, and you also had people like Károly Kernstok, who painted with a classical restraint. Members of The Eight remained figurative painters, they never went as far as, for example, Matisse, who often used colors purely for their own expressive power.

Many of them spent time in Paris and they’re also known as the “Hungarian Fauves.”

It’s true that the artists spent time in France and Béla Czóbel even exhibited together with Matisse. But what’s interesting to me is that most of them actually returned to Hungary. This was just before WWI, when Budapest was thriving. There was a market for their paintings and a stimulating milieu. They collaborated with intellectuals and musicians, including Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, and Béla Balázs (and painted portraits of them).

László Moholy-Nagy is perhaps the best-known Hungarian artist. How much of his art was rooted in his homeland?

Not much, although he knew Lajos Kassák and was involved in his avant-garde publications. Berlin had a huge impact on Moholy-Nagy. Going to Berlin from Budapest in 1920 was like going to New York today – a spectacular city. Moholy was an impressionable young man and this big city and its massive infrastructure inspired him immensely. His early abstract paintings show rail hubs and bridges. Bauhaus Director Gropius saw his works at Der Sturm Gallery in Berlin and hired him to teach at the school.

What’s unique about Moholy’s art?

He noticed things others didn’t. His first wife taught him about photography and soon he lifted photography into the realm of art. His “telephone pictures” were also novel: the idea that he calls an enamel factory, provides the instructions of sizes and color codes, and the factory delivers the final picture made entirely without the physical contact of the artist. This idea of inputs and outputs anticipated our digital universe.

What happened during this time back in Hungary?

There was little space for modernism in the 1930s. The Hungarian state supported the local neoclassical “School of Rome,” because of its political alliance with fascist Italy. This meant conservative style and religious themes in painting. There were some modern movements and artists, though. Kassák turned to “socio-photo,” that is, social photography, depicting workers who lived in poverty, together with Ferenc Haár, Sándor Gönci (Frühof) and many others. There were modernist artists in Hungary during the interwar years but they had to struggle.

For a few short and hopeful years after WWII, modern artists of all affiliations came together under the Európai Iskola banner.

There was a sense of euphoria after the liberation of Budapest in 1945. Artists felt that a new era was coming, where modern art can finally take its rightful place. They staged exhibitions together with French painters, for example. The Európai Iskola had two factions, the surrealists, which included Endre Bálint, Anna Margit, Gyula Marosán, the late Imre Ámos and Lajos Vajda, and the abstracts, with painters such as Tamás Lossonczy and Tihamér Gyarmathy under the helm of art critic Ernő Kállai. The group was banned after the 1948 Communist takeover.

How should we imagine art in Hungary under the Communist regime (1948-1989)?

This period is often lumped together and labeled simply as the Cold War era, but these four decades in Hungary were a time of many very different periods. The retributions after the Revolution of 1956 ended by 1961-62 and that’s when a relative thaw began. In the arts, socialist realism was still the state-supported style, but there was a somewhat more open attitude toward modern art and relations with Western Europe were, very gradually, re-established.

How did modern artists make a living?

Most of them had day jobs. In the 1950s and 1960s several of them worked at Budapest’s puppet theater for example. The way the system worked was that the Ministry of Cultural Affairs (Művelődési Minisztérium) purchased paintings from artists, which were then offered to museums and state-owned galleries. Most artworks were far from modern, but the ministry did, if rarely, buy some from younger and progressive artists, too. Finally, there were a few collectors.

Were they able to exhibit their works?

During the 1960s and 1970s, there were already exhibitions of modern art. Of course, some of these shows were quickly shut down by the authorities, but they were becoming increasingly audacious. Most famous was the Iparterv Exhibition of 1968, where the works of the leading moderns – including István Nádler, György Jovánovics, Ilona Keserü, Imre Bak, Miklós Erdély, Tamás Szentjóby – shattered the state-set boundaries. This too, was shut down after about two weeks.

Did the same art movements take place in Hungary as in the West?

The leading moderns knew what was going on in the world and were influenced by it. Cy Twombly had an impact on Ilona Keserü’s early work, for example. But the young Hungarian artists expressed themselves in their own unique ways. For example, the sculpture of György Jovánovics, Ember (Man), which fused an archaic Egyptian figure with pop-art details, Ilona Keserü’s vivid abstract paintings and erotic color schemes, and István Nádler’s folkloristic abstract.

What do you think of Tibor Csernus and Victor Vasarely, two painters who both became prominent in their adopted home of France in the 1960s?

Csernus was a great artist, who painted realistically but represented the local spirit of Budapest before the 1956 revolution. His style was very different from the officially required optimistic stance. He continued to paint this way even after he emigrated to Paris, noticing small details that tend to stay in the background. He has a painting from a box match, for example, that captures such a banal moment. His later, more esoteric paintings I couldn’t really follow. As for Vasarely, I don’t feel strongly about his brand of op-art. Simon Hantai, however, became very successful in France.

Why do you think Hungarian photographers (Kertész, Brassai, Capa, etc.) enjoy so much more popular success than painters?

Photographers didn’t have to break through the institutional walls that had existed in painting. By the time Hungarian painters appeared on the scene, there were established museums and galleries and canonized painters in France and Germany. Photography didn’t have such deep traditions in the 1930s until about the 1970s.

What are good places to visit in Hungary to see local artworks besides the National Gallery in Budapest?

Most important are the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs and the MODEM in Debrecen, which is an exhibition hall now rather than having its own collection, but there are excellent permanent exhibits also in Kecskemét, Eger, and Győr, just to name a few.