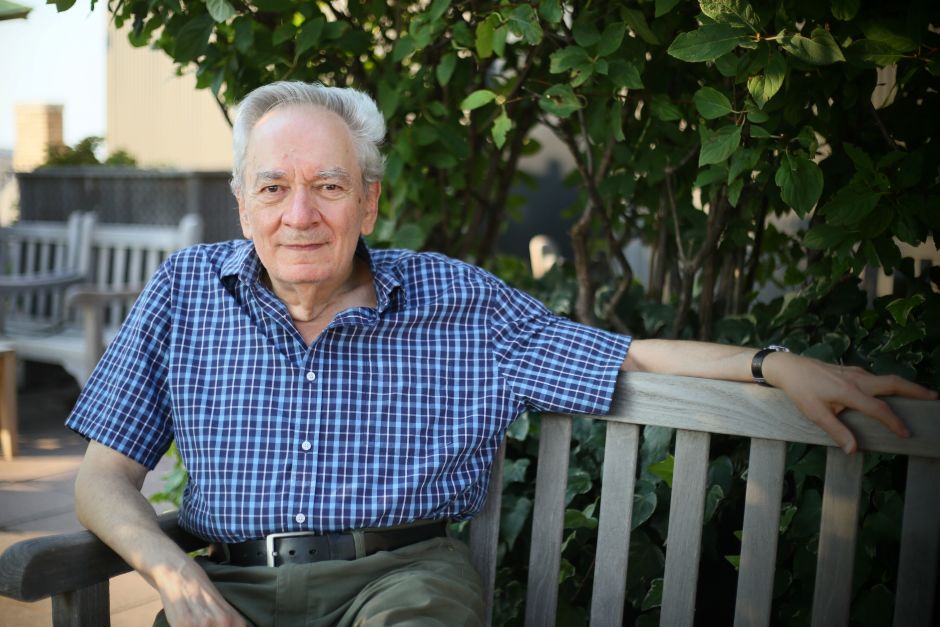

András Koerner is a New York-based architect and a writer who fled Communist Budapest in 1967 and settled in New York City where he still lives. András’s wide-ranging books include the Jewish Cuisine of Hungary, which won the 2019 National Jewish Book Award.

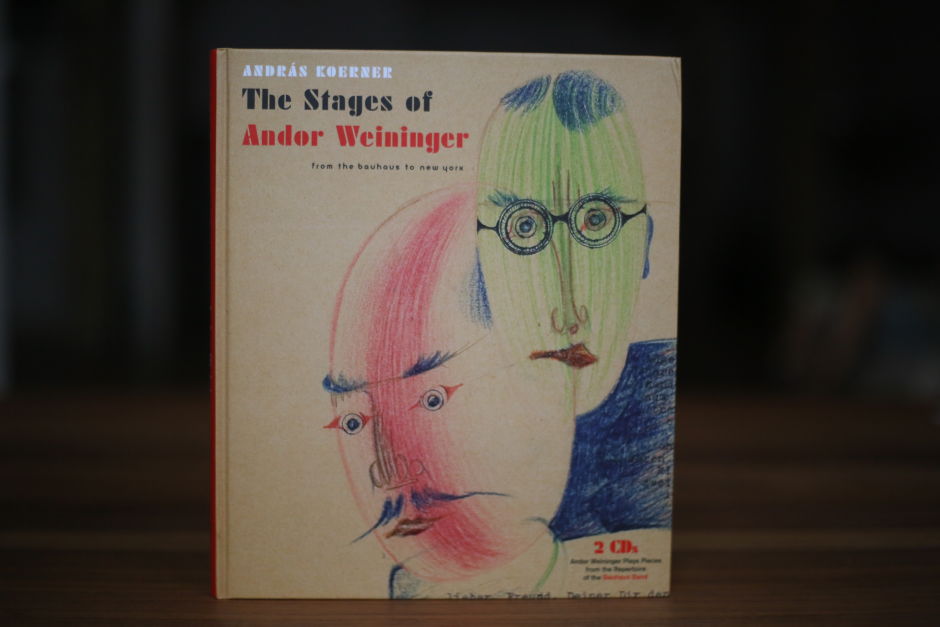

For 16 years, András was close friends with avant-garde painter Andor Weininger (1899 - 1986), who was a student of Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus school in the 1920s. Over the course of this time, Weininger shared countless Bauhaus-stories with András that served as the basis for his 2008 monograph, The Stages of Andor Weininger. During my recent visit to New York, András was kind enough to relay some of those stories to me.

Talk about the early Bauhaus (1919-1923). What was the influence of Johannes Itten?

The Weimar Bauhaus was shaped by Johannes Itten’s mystical beliefs and Mazdaznan cult. He was a charismatic teacher and half the Bauhaus was under his influence, including Marcel Breuer. On his first day at the school, Weininger saw Itten’s followers leave the classroom after a “sermon” he gave. They wore the uniform Itten designed for them. Colorful overalls made from linen that looked like working clothes.

Breuer, who was very thin and pale, appeared in this bright-orange outfit, which Weininger thought was comical (they were friends from Pécs). Later Breuer grew disillusioned by this mysticism.

Theo van Doesburg, the founder of the De Stijl movement, built his own cult among the students in Weimar.

Doesburg, another strong and charismatic personality, badly wanted to become a teacher at the Bauhaus in 1921. When the director of the school, Walter Gropius, didn’t agree to this, Doesburg started a sort of anti-Bauhaus course in Weimar. Weininger was the first to join it, and so did many other Bauhaus students.

Doesburg rejected any illusion of space in painting, and advocated for geometric abstraction. A strict visual language made up of horizontal and vertical elements and primary colors. This was very different from Itten’s mystical teachings and anticipated the second, more rational phase of the Bauhaus introduced by László Moholy-Nagy.

Farkas Molnár. After the Bauhaus, he became the leading modern architect in Hungary in the 1920-30s.

My father [József Körner, one of Hungary’s prominent modern architects in the interwar period – TT] was very good friends with him until the early 1940s, when Molnár took a sharp right-turn politically. After the Communist Revolution of Hungary in 1919, Molnár wanted to become a Red Army soldier. Weininger, on the other hand, did his best to stay out of the Red Army. He respected Molnár’s talent and they were good friends, but he thought Molnár was always drawn to the extremes.

Was Molnár the star student he is claimed to be in Hungary?

He was very talented. His Red Cube house design was exhibited at the Bauhaus’s first major show in 1923 in Weimar. In addition to his studies at the Bauhaus, Molnár also worked at Gropius’s architectural office. But I don’t think he or any other student can be compared to Breuer. Gropius quickly recognized this and plucked him out of the bunch.

What was it about Breuer that made him stand out?

He was a genius. The watercolors he did as a young student were so good that Bauhaus painters were lucky Breuer turned to furniture design and architecture. And don’t forget that he was only in his early twenties when he designed his first tubular steel chairs.

Breuer, Mart Stam, and Mies van der Rohe all designed a cantilevered tubular steel chair around the same time in 1928. Which one is your favorite?

I think Breuer’s Cesca chair is more elegant than Stam’s. But my favorite by far is the one by Mies van der Rohe.

Mies van der Rohe was a heavyset man, and his chair is a big, expansive chair. The frame’s semicircular curved shape takes up a lot of space. It’s less practical than the Cesca. But more elegant.

What was Breuer like as a teacher at the Bauhaus (1924-28) and later at Harvard (1938-46)?

Very different. At the Bauhaus, Breuer showed up once a week and didn’t care much for the students. He was busy with his own designs and building his career. He even made students build parts for his own furniture. Eva Weininger, one of Breuer’s students, was very upset by this even in old age. At Harvard, on the other hand, people loved him. The architect Victor Lundy told me that Breuer inspired them and that he was an inventive and passionate teacher.

Do you like Breuer’s buildings?

Some I do, some not so much. I prefer his early single-family residential houses. They’re full of creative ideas. Some of his later single-family homes are too muscular, over-designed for my taste. Of his later buildings, one of my least favorites is the Armstrong Rubber Company’s Brutalist building in New Haven. The office floors there are hung from a truss in the roof. The building’s shape is striking, but also forced and inelegant.

On the other hand, I do like the Whitney Museum. It doesn’t speak to its Victorian surroundings, but that wasn’t the point. The museum needed a strong character, and Breuer achieved that.

László Moholy-Nagy.

Moholy was even more ambitious than Breuer. He was all about advancing his own career. Here’s an example. Moholy was in charge of the Bauhaus Books, and one of the publications in the series was about the Bauhaus Theater. You have to know that the person who embodied the Bauhaus theater was Oskar Schlemmer. Moholy did a few stage designs outside the Bauhaus, but he had nothing to do with the stage-class there. And yet when the book came out, much of it consisted of Moholy’s and Molnár’s articles and featured only a short study by Schlemmer. By the way, Molnár also wasn’t a member of the Bauhaus stage-class. Schlemmer was furious. Moholy had incredible talent, but also sharp elbows.

Moholy wasn’t very popular among the fellow Bauhaus Masters.

The Bauhaus director Walter Gropius was good at detecting new movements, and by 1923 he wanted to move away from Johannes Itten’s romantic and spiritual notion. This is why he hired Moholy, who quickly started to shake up things. Naturally, Kandinsky and Klee weren’t thrilled when this young guy showed up and wanted to change everything.

What did Breuer think of Moholy?

Like others, Breuer didn’t like Moholy’s show-off style and fondness of self-promotion. They weren’t close.

But Moholy was a very talented artist.

He was like a sponge. I don’t know any other artist so good at absorbing new influences and then quickly making them his own. Moholy was inspired by the Russian avant-garde and his paintings and photos show influences of El Lissitzky and Rodchenko, but his works stand on their own. He wasn’t just an imitator. Moholy’s amazingly quick and successful response to contemporary ideas is almost unprecedented in the fine arts.

What did Weininger think of Walter Gropius?

He didn’t agree with him in everything, but respected Gropius immensely for his essential fairness and for not letting extremist ideologies seep into the Bauhaus. For as long as he could, Gropius kept the school away from both Nazi and radical leftist and Communist ideologies.

Weininger was enrolled in Wassily Kandinsky’s Wall Painting workshop. What was Kandinsky like?

He liked and respected Kandinsky. Like Breuer, Kandinsky didn’t take teaching too seriously in the Wall Painting workshop. He showed up once or twice a week. His lectures at a later course on analytical drawing were notoriously hard to follow. Not because he spoke bad German, but because he expressed himself in an ambiguous manner.

Weininger thought that the Bauhaus had only two masters who were passionate and good teachers: Paul Klee and Josef Albers. Truth to say, Moholy was also an excellent teacher, which Weininger acknowledged in other conversations with me. He also said that the metal workshop under Moholy was the best-functioning at the Bauhaus, because Moholy was able to get commissions for the school.

So many painters in the Bauhaus staff and yet we don’t think of the school that way.

Most students viewed the fine arts as a dated art form. They preferred the applied arts, more practical things. Initially as craftsmen, later working together with modern industries. It wasn’t fashionable to paint for art’s sake. So the students who painted, like Weininger, were hesitant to show their works to others.

Can you talk about Josef Albers?

Albers was morally upright and without the fierce competitive spirit we discussed about others. Later on, after the closure of the Bauhaus, he was bitter at Gropius for always talking about Moholy as the primary face of the Bauhaus’s Preliminary Course. He was right. Albers played an equally important part. I have seen a letter he wrote about this to Weininger.

I don’t think Albers was a great painter, but his teaching at Black Mountain College in the 1930-40s had a big impact on the American avant-garde. People such as Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly studied under him.

Did Weininger get along with him?

Yes, they liked each other and corresponded long after the Bauhaus years. Albers complained to him about the overemphasis of Moholy, because he knew Weininger would lend a listening ear.

Once, when Albers was in New York, Weininger showed him his paintings and asked for advice on how to get an exhibit and sell to museums. Albers recommended that Weininger pick a single painting and make 50 variations of it. That this would bring him commercial success. This was funny, of course, because that’s exactly what Albers himself did, but this approach was contrary to Weininger’s personality.

Weininger organized the Bauhaus Band. What was it like?

He founded and led the Bauhaus Band for years. Weininger’s idea was to perform different folk songs, to reflect in music the Bauhaus’s multi-cultural background. He himself knew many Hungarian and Serbian songs (he was from the south of Hungary where many Serbians lived). This was an avant-garde idea in Germany then. It is similar to what we call World Music today. They gave many concerts outside of the Bauhaus, too.

Who were the members of the Bauhaus band?

For several years in their initial setup: Andor Weininger (piano and singing), Heinrich Koch (bumbass), Hanns Hoffmann (side drums), and Rudolf Paris (big drum). In later years, they were joined or replaced by Clemens Röseler (tenor banjo), Xanti Schawinsky (trumpet), Werner Jackson (drums), and T. Lux Feininger (banjo). The band changed direction when Weininger left the Bauhaus in 1928. It started showing influences of American jazz and lost its “native bohemianism”, as T. Lux Feininger put it.

Did he ever play Bauhaus music to you?

We needed to nag him a little to play for us, but he did, despite stiff, arthritic fingers. He wasn’t a trained pianist, but he had perfect pitch. I organized the amateur tape recordings his wife and daughter made of him playing and singing in old age, and included them on two CDs in my book. I strongly believe that the Bauhaus Band was an artistic creation, a typical Bauhaus product, comparable to the school’s other achievements.

I’m envious you had this incredible access to Weininger for nearly two decades.

It was a magnificent experience. I was always a bookworm and read about these figures, such as Klee, whom I admired, and Kandinsky. But they seemed very distant figures, almost like Leonardo. Through Weininger’s numerous stories over the period of 16 years, the people of the Bauhaus came alive.

Who is your favorite of the bunch?

Walter Gropius had the rare ability to put aside personal grievances for the interest of the school, and for the interest of art. For example, despite the personal blows from Marcel Breuer and Herbert Bayer, he continued to support both of them. He was an upright and virtuous man.

The other is Oskar Schlemmer. He was a fascinating artist – a very good painter, a very good sculptor, and the leader of the highly creative theater workshop. But somehow he is less known than the other Bauhaus masters.