Imre Makovecz, who died ten years ago, created a unique brand of organic architecture in Hungary. His mystical buildings were inspired by nature and folk culture and enjoyed global fame.

When it comes to Hungary, architecture buffs can usually muster up one or two names. The first is Marcel Breuer, although much of his career unfolded in the United States; the second is Imre Makovecz, the founder of Hungary’s influential organic school.

Makovecz came of age when many architects globally started to be disillusioned by the sleek white “boxes” that Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus school popularized. Working for a state-run design firm (Szövterv) tasked with restaurant projects, Makovecz was not yet thirty in 1964 when his first works shocked the local architecture community in Communist-era Hungary. With thatched roofs, dramatically overblown wooden beams, and playful facades, he designed sculptural buildings that seemed like objects from another universe. “What I miss from architecture today, as from other things, are signs of personal character,” he later wrote.

The American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was an early inspiration, especially the way Wright integrated buildings into their environments. Makovecz’s ski lodge in Dobogókő, a popular tourist region outside Budapest, for example, clad entirely in vertical wooden slats, blends beautifully into the forested hilltop. “These days, who cares about the connection between the building’s interior texture and the soil surrounding it? But these things are more important than whether it’s a modernist or neo-brutalist or God knows what style of building,” Makovecz once said. Wood became his trademark, featuring both as structural supports and finishes. His father was a carpenter and the young Makovecz would accompany him to roof renovations, learning about the craft at an early age.

Makovecz viewed his buildings as living creatures, designing them with striking biomorphic shapes. It intrigued him that the Hungarian language (like some others) uses human traits for the vocabulary of a house: facade comes from the word “forehead,” the ridge of the roof from “spine,” the upper ledge of a window from “eyebrow,” and so on. His “humanized” architecture reached its high point with the haunting funeral chapel at Budapest’s Farkasréti Cemetery (1975). Repeating planks of beech wood form the shape of a rib cage, into which comes the coffin — placed symbolically near the heart.

The main influence on Makovecz’s nearly 250 completed buildings was folk culture. He admired ancient civilizations, especially Celtic, and knew about the life of the Hungarian countryside from spending summers as a child with his grandparents in a village in western Hungary. He believed archaic symbols like yin and yang contained condensed folk wisdom and transmitted lessons to humanity about the universe. Esoteric ideas like this weren’t foreign to Makovecz, who believed in the anthroposophic teachings of Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and architect.

In practice, this meant his buildings were abstract structures inspired by vernacular architecture and prehistoric formations. The Sárospatak community center (1972), for example, near the Slovakian border in eastern Hungary, features overblown flowers, tree crowns, skeletons, and primordial creatures. The shape of the Catholic church in the city of Paks originates from two symmetrically placed “S” signs, a symbol he traced back to Celtic and Hungarian tribes.

His buildings created a mythical and mystical world. He liked to compare his own method to that of Béla Bartók, one of his idols: Just as Bartók did more than transcribe folk songs into compositions, so did he distill the essence of folk architecture into the 20th century.

Makovecz also thought that too little was said about the pagan influences on European culture. He felt most comfortable with architecture that predated the Greeks and the Romans, preferring “a building that looks like it was formed by the forces of nature to one that’s based on some theory, even if made from the best materials.”

This mindset shines through the group of his campsite buildings in the Visegrád woods (1978) near the Danube. Set on a quiet hillside, the scattering of ambiguously shaped wooden structures — gently sloping huts and semi-circular open-air yurts — have an intense plasticity, and the absence of a clear boundary between inside and outside lends them an archaic air.

Since pagan religions were compatible with Christianity in Makovecz’s mind — they were both seeking the same truths — his buildings fused symbols of the two. For example, the moon and the sun, signifying darkness and light, appear beside the Christian cross atop the three towers of the church in Paks (1988-1991), a small town in southern Hungary. While this made Makovecz a controversial figure within the Church and a public enemy of religious fanatics, it didn’t stop him from winning commissions for churches, chapels, and funeral homes throughout his career for various denominations.

By the 1970s, the traditional way of life in the Hungarian countryside was vanishing and its communities disintegrating. Makovecz and his colleagues set out to build new community centers in small, neglected Hungarian villages, hoping that more dignified buildings may slow the decline and bring people together. Budgets were laughably low so they used whatever building materials were locally available. “We’d wander the forest, looking for logs,” Makovecz later remembered. Once the designs were finalized, they relied on the locals for construction since it cost no money and fostered a communal spirit.

Recently, I visited two of these community centers in western Hungary. They seemed lively with many events on the calendar such as folk dance performances and embroidery workshops. Both buildings housed a small library upstairs. In Zalaszentlászló (1980), locals were preparing to host a group of visitors from Manneville-sur-Risle, their sister city in France. In Bak (1985), they had an exhibit of the season’s fruits and vegetables harvest. It was hard not to feel that these places accomplished Makovecz’s mission.

But these visits also brought to light what many consider to be the main flaws of Makovecz’s buildings: impractical spaces and difficult maintenance. Although built just over thirty years ago, Bak’s community center has had two renovations already and a number of interior remodelings. The open floor was partitioned because it was impossible to carry on two events at once. The performance stage, still today, overlooks half a dozen columns that obstruct the audience’s view.

The height and the unusual shape of the roof means that heating is expensive, maintenance costly. There were similar challenges with other buildings. The Pázmány Péter Catholic University announced last year that they were moving out of their Pilis campus, less than two decades after Makovecz built it (there were also other reasons behind the decision).

Charismatic, ambitious, and opinionated, Makovecz was a natural leader and by the late ‘60s a group of acolytes gathered around him (he was also a notoriously difficult person, being quarrelsome and easily upset). He organized group discussions and lectured about organic architecture. By the mid ‘80s, there were about forty architects across Hungary who belonged to his “organic school,” many of whom — Dezső Ekler, Ervin Nagy, Tamás Nagy — later became prominent in their own right.

Some joined Makovecz’s private practice, Makona, others were more loosely associated. Organic buildings started to appear also in neighboring countries like Slovenia, Slovakia, and Romania, especially where meaningful Hungarian communities lived. “Organic architecture became a way to self-identify for Hungarian minorities,” Andor Wesselényi-Garay told me, who is an architecture critic and professor at Széchenyi István University.

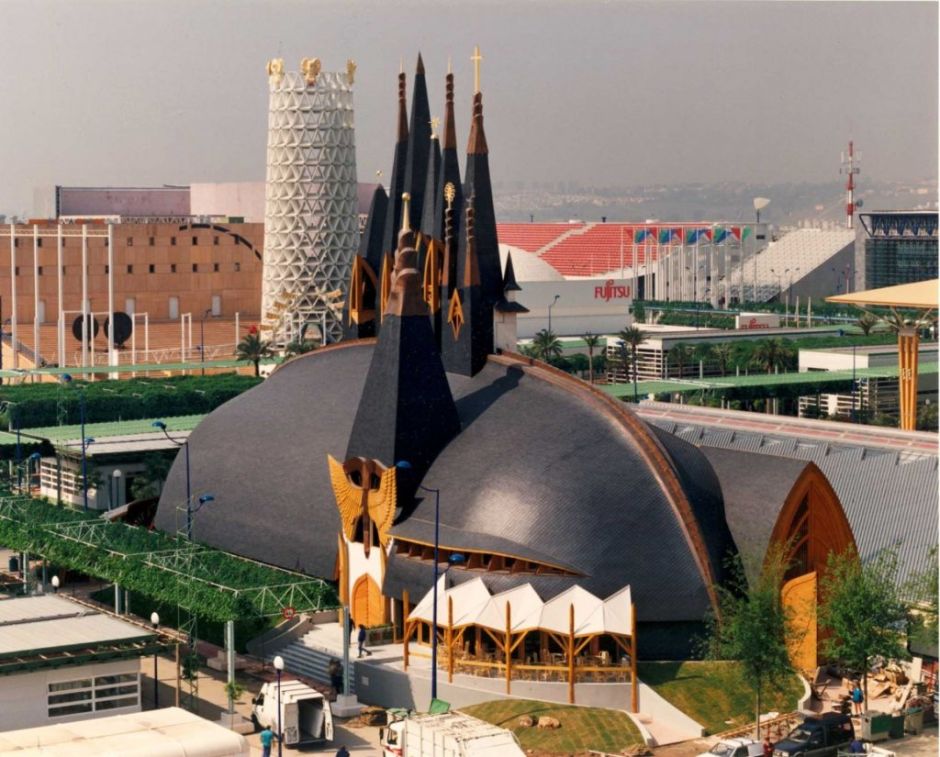

By the 1980s, Makovecz was well known at home and abroad. Makovecz exhibits were staged in places like Paris, New York, and Berlin and books written about him. Foreign architects came to Budapest to do internships at Makona. His career reached its high point during the World Expo in Seville. “Imre Makovecz's Hungarian pavilion, widely regarded as the most inventive structure at Expo '92 here, soars free from the fair's architectural cacophony like some dizzy fantasy,” wrote The New York Times.

He bisected a dramatic wooden structure into east and west sides, keeping a walled-up narrow path in between, which was his way of symbolizing Hungary’s uneasy role historically as the protector western Europe, for example from the Ottoman Empire. The building, topped with seven church towers, was packed with other hidden meanings. Prince Charles was so taken by the tree of life, an actual tree with its roots exposed under a glass partition, that he sent an earnest note of congratulations to Makovecz.

In 1997, following people like Kenzo Tange and Norman Foster, Makovecz was awarded the gold medal of the French Academy of Architecture. (Years later, when Frank Gehry visited Budapest, he wished to meet Makovecz in person — a quick, heartfelt rendezvous was quickly arranged.)

While Makovecz basked in the international limelight, his buildings were often misunderstood. “The Hungarian organic movement has often been grouped together with postmodernism internationally, but the two are rooted in very different philosophies,” said Wesselényi-Garay. “Instead of the playfulness of postmodernism, Makovecz’s architecture had a deeply serious narrative. He believed architecture could make the world a better place and that his buildings connected people with nature and the earth with the sky.”

By the early aughts, Makovecz’s architecture lost some of its elemental power and his buildings started to show repetitions of earlier works. At the same time, he became more political in post-communist Hungary (Communism ended in 1989) and his impulsive outbursts often had nationalist overtones.

He railed against globalization, American cultural dominance, and the Hungarian liberal elites who sold out to international financial interests. These views landed him on the political right (he was a great admirer of Viktor Orbán) and cast a cloud over his architectural legacy even before his 2011 death. Today, many liberals in Hungary are dismissive of or uninterested in Makovecz's architecture because of his politics.

The Orbán regime, not surprisingly, has made it a priority to preserve Makovecz’s legacy. In 2017, the Prime Minister himself inaugurated the Makovecz Center & Archive, a small research center inside the house Makovecz had built for himself. Last year, the government allocated more than €35 million for the maintenance of thirty Makovecz buildings, which came on top of funds provided for the construction of several new buildings that Makovecz designed before his death but were never built (there’s even talk of erecting the gigantic church that was going to be Makovecz’s victory lap).

With Makovecz’s passing, the organic movement lost its key figure but hasn’t disappeared. Its mentorship program (Vándoriskola) and longstanding publication (Országépítő) are still around, and a class about organic architecture was recently introduced at the Budapest University of Technology.

“Architects of the organic school are active outside of Budapest, doing a lot of winery renovations in the Tokaj region for example. There’s a bit of stylistic uncertainty at the moment: they don’t try to mirror Makovecz’s exuberant brilliance and instead follow a more restrained, regional style with lots of brick,” said Wesselényi-Garay, who considers Attila Turi the leading figure currently.

While it seems that Hungarian organic architecture is here to stay, few people would argue with the statement made back in 1987 by Dezső Ekler, one of Makovecz’s most talented students: “As with Frank Lloyd Wright, he didn’t have a predecessor and his architecture can’t be continued.”