Barry Bergdoll is a professor of art history at Columbia University and one of the seven-member jury for the Pritzker prize, architecture’s highest honor. Between 2007 and 2013, he was the chief curator of architecture and design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). He is the leading scholar of Marcel Breuer, the Hungarian-born architect and furniture designer. Barry recently spent a few days in Hungary to visit Pécs, Breuer’s birthplace; to give a lecture at the Budapest University of Technology; and to meet young local architects.

Was there a highlight to your Pécs trip?

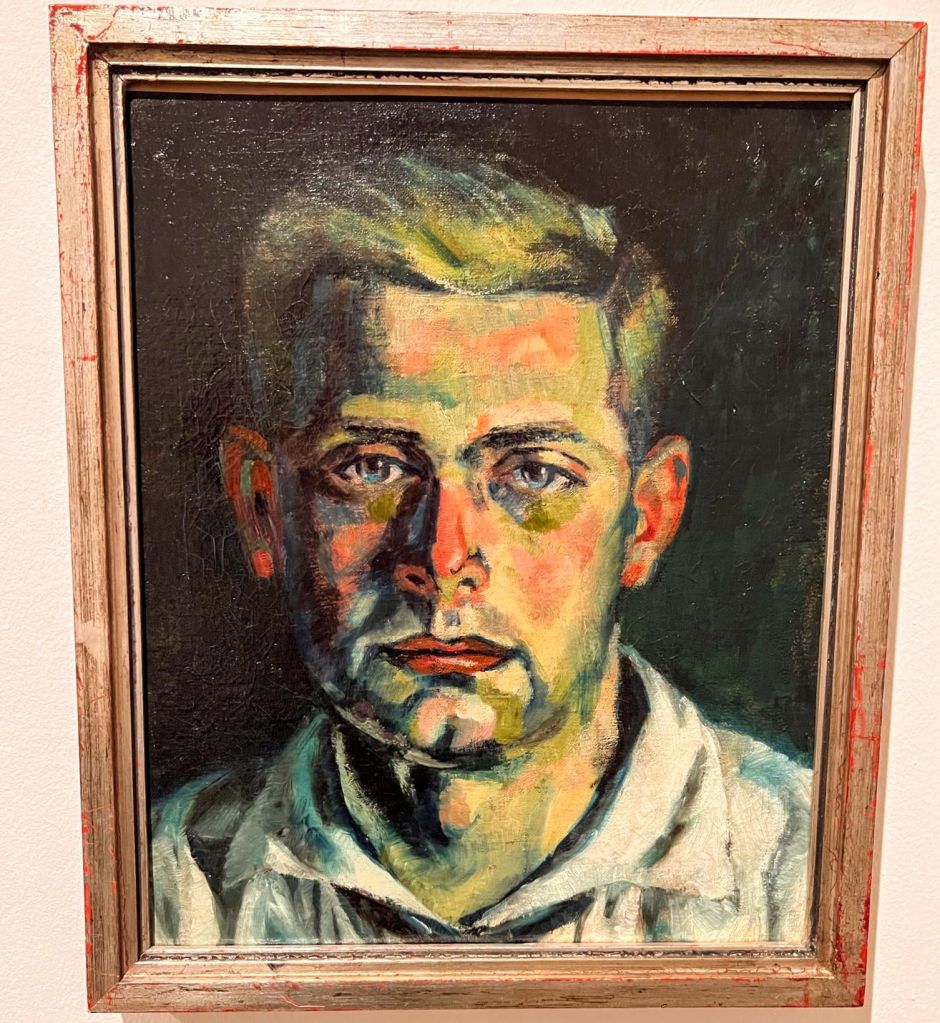

I can’t get over that portrait the 17-year-old Marcel Breuer painted about his friend... This is a painting by someone who is completely aware of what’s going on in European art; in terms of color, shadow, and how to disassociate color from representation. My shock was not simply that he is such a great painter at a young age, but that he aspires to create a new kind of art. In this painting alone, you can see why he didn’t like the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and chose the Bauhaus instead.

Which part of Budapest’s architecture did you find most interesting?

The unbelievable scale of all these buildings. The ambitions of this city are written into the scale of everything. On one level, it’s the Viennese Ringstrasse, but it feels more massive and ambitious. Not just Andrássy Avenue; the side streets are equally grand. The Pest side is a fabric of grandeur.

You’re referring to the consistent Revival-style architecture.

Yes and no. Some buildings in Budapest, as you say, are completely in-tune with the 19th-century Viennese desire to create a monumental representation: houses that look like supersized Renaissance palazzos of a wealthy Medici-type magnate (they’re multi-family buildings in fact).

But next to them, you have buildings incorporating Hungarian folklore themes and tiles. Every bit as monumental in their scale and proportioning, but in a completely different architectural language. Those by Ödön Lechner and many others.

We toured the Hungarian National Museum (1837-1847) yesterday. Is your interest in Neoclassical architecture specific to Budapest?

It’s the type of architecture that appeals to me. We speak about the International Style of the 1920s and 1930s. Neoclassical architecture in the first half of the 19th century was the international style of Europe then. There’s nothing specifically Hungarian about that building.

You said you liked the Lutheran Church (1799-1808) on Deák tér.

This is a bit arcane, but I’m fascinated when architects are interested in the very primitive origins of classical architecture. Mihály Pollack, who did the Lutheran church in Budapest, is clearly aware of the debates of early Doric temples and how to deal with its massive proportions and primitivizing details.

The Revival architecture of late 19th-century Europe is maligned in the present day, but you seem to find merit in these buildings.

I can’t explain how I became fascinated by Revivalism. Partly it’s the contrarian in me that wants to like what other people don’t. The Revival styles in the late 19th century were not succeeding one another, but always competing with one another [Baroque Revival vs. Renaissance Revival, for example]. They were reflections of the cultural and political battles of the 19th century and I’m interested in the messages people are sending in their choice of style.

What is it that catches your attention in a Baroque Revival building from the 1880s?

It's reappeal to emotion. It wants to overwhelm the spectators and the citizens who encounter these buildings.

Moving to Vienna for a moment, is it fair to regard Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos as the fathers of modern architecture?

I don’t think that’s a contested idea. Adolf Loos is a particularly interesting case. He wasn’t woven into the first heroic stories of modern architecture as they were being made. For example, you don’t find Loos in the 1932 modern architecture exhibition at the MoMA. He was left out, even though many of the key ideas of the International Style are already present in Loos. He was rediscovered in the 1970s as somebody people should’ve paid attention to.

What’s special about Loos?

The spaces of his interiors combined with the deliberate plainness of his exteriors is extraordinary. You think of Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe making these incredible open spaces on one floor: absence of walls, seeing over one partition to another. With Loos, he is doing all this in section – as you move from one floor to another. What he called his Raumplan.

Is there a reigning architectural style today?

I don’t think at the moment, in 2023, people are talking so much about an ism: some new universal truth to get behind. Perhaps the last declared paradigm was associated with Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher’s parametricism – playing with algorithms and computers to generate themes and variations in design. I think it was more parodied and made fun of than taken seriously.

What then defines architecture today if not a universal style?

Every issue under the huge umbrella of sustainability. Architecture has to respond to the climate crisis. That is the cutting edge. In 2021, the Pritzker jury gave the prize to Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. They have made more renovations than new buildings. That was a recognition that we have to work with what’s already here and not being wasteful.

This changes the role of the architect.

Meaningful architecture will be much less heroic than in the past. The architect can’t always be the creator of some brilliant new thing. The focus shifts to optimizing what already exists. The architect becomes a problem solver rather than a heroic form-giver.