Bauhaus, the influential German art school, had a profound impact but less austere architecture came to shape 1930-40s Budapest.

Modern buildings and their offsprings dominated global architecture for the better part of the past century. Clean lines, sleek geometric shapes, and plain surfaces have become the norm in architecture: hardly a day passes without a fashionable design magazine featuring a mid-century modern or brutalist building, both of which originate in the modernism of the 1920s.

Modern architecture can be traced back to the Viennese buildings of Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos, to the Soviet constructivist movement of the 1920s, to the De Stijl group in Amsterdam, but none became as influential as the Bauhaus, the short-lived art school in Germany. Despite existing for only 14 years — before the Nazis forced it to shut down in 1933 — the “Bauhaus style” is still a label for pared-down, radically spare white buildings stripped of ornaments.

The first modern buildings in Budapest appeared in the late 1920s in part thanks to young architects who returned to Hungary after attending the Bauhaus. The leading advocate of the local movement was Farkas Molnár, a star student and a colleague of the school’s founder, Walter Gropius (Hungary was well-represented at the Bauhaus with a total of 26 students and teachers). At home, Molnár organized like-minded architects into the local chapter of the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) and actively spread the modern principles through publications and exhibits.

The roots of the modern movement go back to the early 20th century when architects started to drop the elaborate decorations of the Revival and the Art Nouveau movements in favor of simpler buildings. The emphasis shifted to reaching harmony between form and function. Less became more, in line with the famous credo of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, one of the Bauhaus’s directors. New building materials like steel-reinforced concrete could bridge longer gaps, creating flexible living spaces and better-lit homes.

These new stylistic principles were often infused with political ideology. The rapid industrialization of the late 19th century created impoverished working classes in cities and made social inequalities more visible. This prompted architects to completely break with the aesthetics of Victorian bourgeois individualism and channel the art of modernism into public housing and city planning.

But the modern style was far from acceptable in the Budapest of the 1920s. Molnár, who had to earn a degree at the Budapest University of Technology before being permitted to practice architecture, drew the contempt of university professors and right-wing student clubs with his Bauhaus-inspired drawings and design plans.

In fact, the political climate between the world wars discouraged avant-garde art movements in Hungary. Following the short-lived Soviet-style republic that rose to power during the post-war chaos in 1919, all left-leaning art movements were accused of Bolshevik or cosmopolitan ideology by the conservative nationalist regime of Miklós Horthy, which ruled the country from 1920 to 1944.

Architects who belonged to the CIAM were all but excluded from public tenders. Even worse, when Molnár and his colleagues made an exhibit criticizing the Hungarian government’s public housing policies, the event was canceled and the organizers prosecuted for inciting public unrest.

Instead of modern architecture, the state favored the Baroque Revival style of the 19th century. Outdated as it was, it evoked a happier era and aligned better with the traditional tastes of the political and aristocratic establishment. When Marcel Breuer saw these political headwinds, he left Hungary, leaving behind the architecture practice he had set up with Molnár and another CIAM member, József Fischer. Breuer later became one of the most recognized figures of modern architecture and furniture design in the world. One can only wonder what this group might have been capable of in a different political climate.

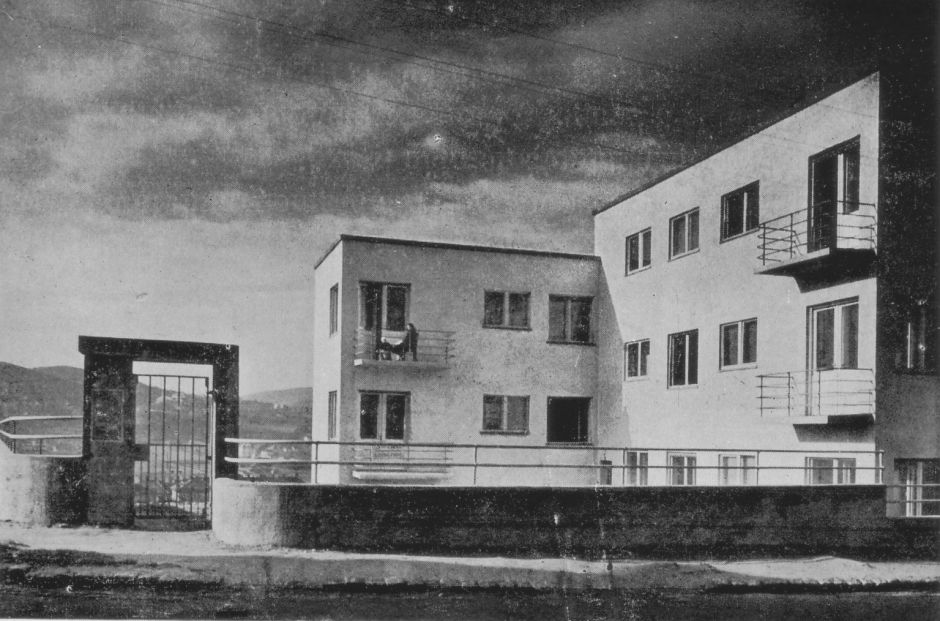

Not all countries in Central Europe were opposed to modern architecture. The first modern buildings in Czechoslovakia appeared as early as 1925. Unlike Hungary and Austria, Czechoslovakia was on the winning side of World War I and it enjoyed a booming economy and a stable political environment under the philosopher-statesman Tomáš Masaryk.

“The Czechs came closest to achieving a western-style democracy and for them modern architecture expressed this optimism and catch-up to Western Europe. Paradoxically, the gleaming white modernism of hospitals, schools, shopping centers, and industrial facilities became a symbol for both Czech national identity and a commitment to western values,” writes András Ferkai, a leading architectural critic in Hungary, in a 1998 essay titled “Cultural Identity and The Modern Movement in Central-Eastern Europe.”

In Hungary, modern buildings in the late 1920s were relegated to private commissions. And even those were hard to come by. In an effort to promote modern architecture and design, in 1929 Molnár and his wife held an open house of their new one-bedroom apartment on Budapest’s Gellért Hill.

Everything about the three-story building, which Molnár designed, looked wildly different from what people had been used to: its flat roof and plain facade stood out from afar. Inside, there was Bauhaus furniture complete with a disk of opaque ceiling lamp, Breuer’s tubular steel chairs — including the famous Wassily Chair — and Molnár’s custom-made desk and cabinets. By taking advantage of built-in cabinets, multifunctional furniture, and massive windows, Molnár extracted more space and light from this small place than had been thought possible.

Mirroring the increasingly pro-Italian foreign policy of Hungary, Mussolini-era Roman architecture also left its mark on Budapest. Between 1928 and 1938, the government funded a postgraduate scholarship program for Hungarian artists, including architects, who studied at the Hungarian Academy of Rome (located inside the stunning, Borromini-designed Palazzo Falconieri).

This was when people like Bertalan Árkay were exposed to the Novecento-style that mixed the classical and the modern: overblown arches and columns set against the background of smooth, symmetrical white surfaces. Árkay’s Roman Catholic church in Városmajor Street is the most successful Novecento-influenced building in Budapest, complete with a standalone bell tower, limestone colonnade, and contemporary artworks. Gyula Rimanóczy, another member of the “Roman school,” designed several landmark buildings, including the immense Postal Office in District 7’s Dob Street.

Several talented architects came also under the sway of Le Corbusier’s ideas by reading about him in Hungarian publications and some of them — including Károly Dávid, János Wanner, and János Weltzl — even trained at his office in Paris during the 1930s. There are many elegantly modern buildings in Budapest fitted with horizontal windows, hoisted on slim concrete columns, or decked out with flat rooftop gardens that bear obvious inspirations from Le Corbusier.

The most interesting large-scale housing development of the early 1930s was in Napraforgó Street, a leafy area on the outskirts of Budapest. The private developers, Fejér & Dános, hired a motley crew of 18 leading architects that included both the radically modern Molnár, but also the notoriously conservative university professor, Gyula Wälder, to build 22 small houses for middle class families.

The project was a resounding success. At its completion in 1931, the charming side street was flanked by two-story, flat-roofed family homes, each slightly different but fitting into a modern aesthetic. The houses were sunny and came with fully equipped kitchens and bathrooms. Unfortunately, some of them have since been neglected, parceled up, or unrecognizably rebuilt, but the area has been coming back to life recently thanks to increased awareness of its historical importance.

By the early 1930s, modern architecture was slowly spreading into the mainstream. Like elsewhere globally, its social program largely gave way to commercial motivations: instead of functional public housing, architects designed upscale homes for upper middle-class clients enthralled by the novelty of modern architecture and its minimalist aesthetics. The new style was especially popular among Budapest’s left-leaning, often Jewish elites, for whom it was a status symbol in the face of the antiquated Baroque Revival style.

Wealthier clients, who by the mid-1930s also included large corporations and the Hungarian state, expected more than “simple” boxes covered in white plaster. They wanted eye-catching jewels that convey prestige. The austere, linear exteriors softened, yielding to lighter, more dynamic, round shapes. Expensive building materials like limestone and shiny marble appeared on facades and in staircases. Inside, the four and five-bedroom apartments and oversized executive suites came with custom-made rubber floors and exquisite wooden and bronze and nickel finishes.

Not surprisingly, these upscale buildings from the late 1930s and early 1940s are most popular today among fans of modern architecture. Many were so-called pension fund apartments, whose owners used the rental income to pay benefits to their retired employees. The crown jewels are Dunapark Apartments and the Manfred Weiss Pension Fund Apartments, both designed by the architecture duo of Béla Hofstätter and Ferenc Domány.

The graceful, limestone-clad buildings of Béla Barát and Ede Novák are also among the most successful from this era. While modern buildings are scattered across Budapest, the area around Szent István park in the Újlipótváros neighborhood has the highest concentration thanks to a sweeping real estate development there between 1933 and 1943.

Impressive as they looked, these buildings had little connection to the original ethos of modern architecture and the Bauhaus. Molnár and his colleagues found these luxury buildings fashionable but modern only in a narrow sense. “A casual observer might think these are modern houses,” wrote Molnár at the time, “but modern homes have to be so primarily from within — the rooms responding to the needs of the inhabitants rather than those of the facade.”

Ironically, Molnár himself shifted to a more playful brand of modernism over time. His most successful work is the Dálnoki-Kovács Villa from 1932, a modernist eye-candy tucked away on a residential Budapest hillside and featuring two roof gardens and streamlined cylindrical shapes. The building feels so contemporary that it’s hard to believe it was built almost a hundred years ago.

With the advent of World War II, the pace of new constructions slowed. During the post-war restoration, modern architecture enjoyed a few short years of unrivaled dominance. That came to a halt in 1951, when the Soviet-controlled Communist regime banned the “Western-influenced” modern style and designated socialist realism the official art form across Hungary. So ended the first period of modern architecture in Hungary, which was to resurface in the late 1950s. Farkas Molnár was no longer around to see this: He died tragically at the age of 47 of wounds he suffered when a bomb exploded near his Budapest home in 1945.