His mother’s memories of a childhood spent in small town Austria-Hungary led András Koerner to a prolific late-life career writing on Hungarian-Jewish culture and food.

On the last Friday of each month, half a dozen graying Hungarian-Americans gather at a Chinese restaurant on New York’s Upper West Side to socialize (since the beginning of the pandemic, they have taken a break). It’s an impressive group of intellectuals who came to America as young adults. These meetings, which I have joined a few times in recent years, blend witty anecdotes and razor-sharp political and cultural observations. It was over a cup of wonton soup here in 2016 that I met the writer András Koerner.

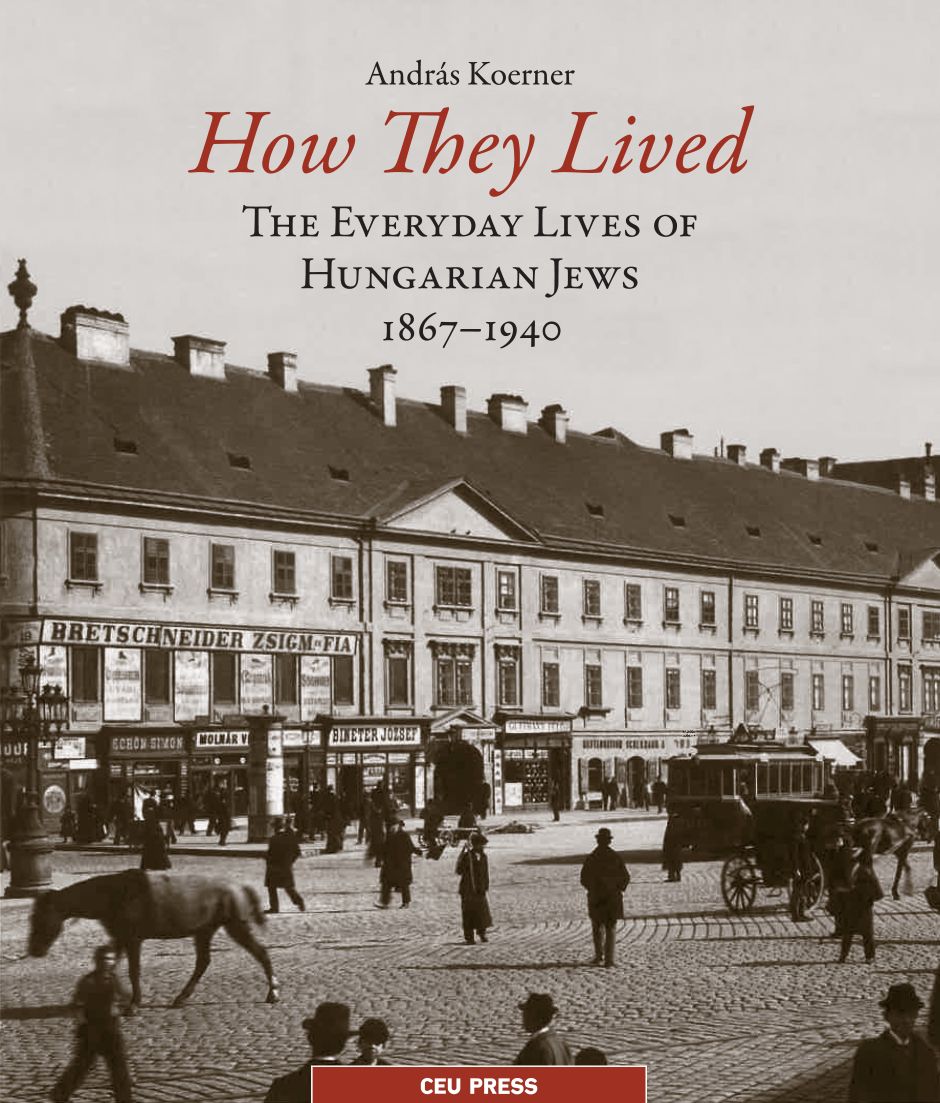

Koerner, who turned 80 last month, left Budapest 52 years ago and is now a leading expert of Jewish-Hungarian culture and food. His best-known book is How They Lived, two-volumes of essays detailing the lifestyles of Hungarian Jews between 1867 and 1940. About twenty percent of Budapest’s residents were Jewish at the turn of the century, and many Hungarian Jews regard this period as a golden era. Koerner’s deeply researched and vivid portrayals bring alive this long-vanished world, aided by hundreds of photographs peppering the text.

Koerner’s most groundbreaking work, though, is on Jewish-Hungarian food. He has become a leading authority on the subject, and he pursues his research with scholarly rigor. In 2019, his contribution to the field was recognized in the United States when his book, the Jewish Cuisine in Hungary, won the prestigious National Jewish Book Award in the Food Writing & Cookbooks category.

The most surprising part: Koerner was 64 years old when he first published a book. To better appreciate his accomplishments, it’s worth revisiting the events that led to this late-life writing career.

Koerner fled Communist Hungary in 1968 and settled down with his wife in New York, where he worked as an architect (his father, József Körner, had been a pioneering modernist architect in Budapest). It wasn't until the 1980s, when things started to ease in Hungary, that Koerner was able to safely travel back to Budapest to visit his mother, by that time ailing and widowed. The two of them previously had a fraught and distant relationship, but Koerner hoped to finally break the ice by interviewing her about the events of her life. The project was a success, and over the next seven years he spent countless hours recording her memories.

Koerner’s mother grew up with her grandparents in a small western Hungarian town in the final years of Austria-Hungary in the 1910s. They were the last members of the family to live by Jewish traditions: they kept a kosher household, performed mitzvahs (good deeds), and planned their lives around the Jewish holidays. Koerner’s mother recalled in brilliant detail their ritual-filled lives, which to her as a young child sometimes seemed comical.

The recordings prompted Koerner to reflect on his own relationship with Judaism. His parents had raised him in a secular and assimilated household in Budapest — they didn’t keep kosher, didn’t go to synagogue, and even celebrated Christmas. Of course this mattered little to the Hungarian Nazis, who herded the four-year old Koerner, along with his father and grandmother, into the Jewish ghetto of Budapest in December 1944. The ghetto was liberated by the Soviet army before its residents could be deported.

Koerner began to live a double-life of sorts in New York. During the day, he practiced architecture and spent time with his family. In the evenings, he’d transcribe the recordings and educate himself about Jewish traditions and their meanings. Books about Jewish history and culture soon filled his bookshelves.

Koerner’s first book, A Taste of the Past, was published in 2004 and borrows from his interviews to bring alive the 19th-century household of his great-grandmother (Riza néni): the chicken-filled courtyard; the pantry stuffed with pickles and preserves; the frenzied preparations preceding Sabbath meals. It also includes a hundred recipes from Riza néni’s handwritten recipe collection dating back to 1869. It turns out, this historic document contains the first written record in Hungary of standard Jewish dishes like cholent, kugel, and matzo ball soup.

The recipes come with Koerner’s helpful cooking instructions and commentary. We learn that most dishes were adopted from the local Christians and adjusted for kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws. For example, the reason Riza néni used ground walnuts or almonds instead of flour in some of her cakes was to keep them kosher for Passover, when grains with leavening agents are forbidden (chametz).

By the time his next book was published on the subject in 2017, the award-winning Jewish Cuisine in Hungary, Koerner had amassed an enviable wealth of knowledge and collection of Jewish cookbooks from around the world (the foreword was written by the prominent scholar of Jewish studies, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett). Later this year, he plans to release a book of short studies setting the record straight about the earliest Hebrew and Jewish-Hungarian cookbooks. This work is intended for a narrower, more scholarly audience, but Koerner’s books are far from dry or academic; he distills his immense knowledge into an approachable first person narration.

“I have a lot of respect for András,” said Tibor Rosenstein, the owner of Rosenstein, a famous Jewish-Hungarian restaurant in Budapest. “He’s passionate and finds information from so many sources. His first book reminded me of my own grandmother’s household in terms of the atmosphere and the dishes. When he comes to our restaurant, we always have a good chat.” When I asked what Koerner usually orders, he said the cholent and the sour veal lungs with bread dumplings (szalontüdő).

Koerner’s intellectual interest extends far beyond food. In 2008, he wrote a book about Andor Weininger, a Hungarian painter, graphic artist, set designer, and a graduate of Germany’s famous Bauhaus school. The sweeping monograph, The Stages of Andor Weininger from the Bauhaus to New York, reveals Koerner’s own vast learning of art history and also contains bits of juicy Bauhaus-related gossip. Last year, he published a book in Hungarian (Költők a kabaréban) about the role poets played in the evolution of Hungarian cabaret in the early 20th century.

One might wonder how Koerner finds time for all this, especially at his age. He says he works about ten hours every day, writing in the morning and researching and answering emails in the afternoon. When in Budapest, he camps out at the Széchényi Library and the Budapest City Archives, peering through documents. Thankfully, his superhuman pace shows no signs of slowing. When I recently asked him about his plans for the new year, he said he hopes to write about his experience working for the legendary industrial and furniture designer George Nelson in New York in the 1970s.